Stephen Cox | Staff Writer

I had run out of lined paper for college and searching my room for more, my eye eventually fell on an A4 pad on my shelf. The copybook looked unused from the outside. However, on opening it I found it was half-full of old lecture notes and revision from almost exactly two years ago, as I was preparing for my first year exams.

You probably thought were pretty good at the time—and wonder how you ever got away with writing such rubbish in your essays

Reading old college work is curious. You can’t help but smile at your own cringe-inducing points—which you probably thought were pretty good at the time—and wonder how you ever got away with writing such rubbish in your essays. Stranger still is the effect this involuntary memory has on you; I found myself, as a cynical third year, almost wishing for a return to the callower days of Junior Freshman life.

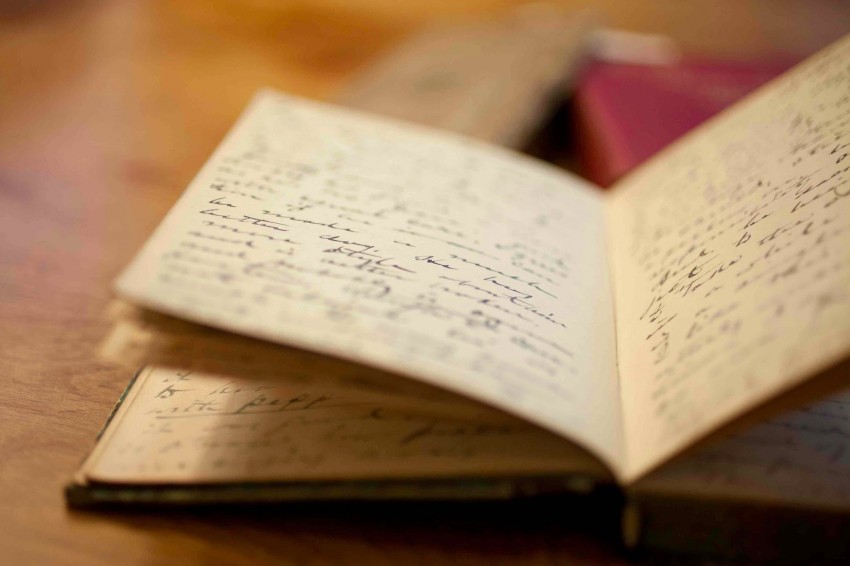

Nonetheless, finding the old notes wasn’t enough; I wished I had something more to go on, something to intensify the nostalgia rush. Of course, reliving this time would have been easier had I been inclined to keep a diary back then. This led me to consider what moves us to record our daily lives, and whether there is any place for the old-fashioned, handwritten diary today. In a world where handwritten letters are a novelty, is there any place left for cursive chronicles of everyday happenings? Certainly the Internet has had a large role in the waning influence of the personal journal. When blogs and web diaries meet the same needs, when typing is so much quicker than writing by hand, what is there to say in defence of the old-school journal?

It is unclear if my lack of devotion to the diary is connected to the instant messaging culture of today

I find there is something pleasing about the pen to page action carried out in writing, something that will hopefully ensure the future of personal scribbles in the digital age. That said, keeping a diary requires discipline. I’ve always liked the idea of keeping a transcribed account of my day-to-day life, but my attempts to create one have, thus far, been largely unsuccessful. My first try was inspired by reading the first Adrian Mole book at eleven or twelve, but my attempts to emulate one of fiction’s most amusing diarists was abandoned after a few days. My most recent effort, a reading journal, was begun only as a bid to aid my terrible memory for the plots of novels; I’ve not even been reading much of late, and I still have two to fill in. A notebook I kept during my Erasmus last year turned out slightly better. However, after writing entries faithfully during the first term, there was a grand total of three passages to account for my last five months in Spain, my ebbing enthusiasm steadily killing the notebook off. It is unclear if my lack of devotion to the diary is connected to the instant messaging culture of today. Diaries certainly require patience—perhaps I’m just not cut out for the methodical dedication needed to keep one.

Written accounts of routine events have been kept all over the world for thousands of years. Possibly the most obvious example today is that of Anne Frank, whose compiled, posthumously published accounts of life in hiding from the Nazis made her famous throughout the world. That Diary of a Young Girl continues to be read and studied is testament to the power personal records can have; even a collection of the most humdrum details can make for entertaining and heartrending reading. The best-known early modern diarist was Samuel Pepys, whose decade’s worth of journals vividly describe life in mid-seventeenth century London. Pepys’s use of a secret code for the frank depictions of his extramarital affairs underlines the function of the diary as a highly personal device, a place where we can convey our innermost thoughts; whether he would have wanted the diaries in public circulation is another story.

Issues that seemed earth-shattering at the time are often exposed as trivial with the benefit of hindsight

Numerous authors and public figures have kept diaries that were later published, sometimes after their death. While most of us don’t have future publications in mind when we’re putting our prosaic scribblings to paper, I suspect that at least some of the desire to record our lives is so we can read over them a year or two later and laugh, usually at ourselves. I flick through my Erasmus half-diary from time to time and chuckle at my bumbling attempts to settle in to life in another country. Issues that seemed earth-shattering at the time are often exposed as trivial with the benefit of hindsight. Maybe rereading old journals or even old homework is just us trying to convince ourselves of our greater maturity, of being cooler than we were at the time of writing. Speaking for myself, I can’t help but feel that, since I scrawled those French grammar notes back in first year, in some ways not all that much has changed.

In Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’, Gwendolen Fairfax quips ‘I never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read in the train.’ Maybe not every diary’s purpose is to scandalise, or even to be interpreted by their author or by others. Nonetheless, the reading (or rather, rereading) experience they offer is strangely enjoyable. I am conscious of extolling the virtues of a procedure in which I have relatively little practice; after waxing lyrical about the benefits of keeping a diary, perhaps I owe it a return with new enthusiasm.