A major question that is rarely asked of third-level students is why exactly they attend university. Do they attend to receive training in a specialised skill or vocation for a deep knowledge of a particular subject or as a means of expanding their mind? Or do they simply go to university because it is what their peers, their family and society expect of them?

According to the Central Statistics Office (CSO), third-level attendance has increased by 105 per cent between 1990 and 2004. The Irish Universities Association (IUA) claims that one in 22 Irish residents is a full-time university student. Yet, we are beginning to notice a problem with third-level education in Ireland, particularly with universities. A Higher Education Authority (HEA) report in January revealed that Trinity has a dropout rate of 7 per cent, the lowest in the country, while NUI Galway and the University of Limerick (UL) see 13 per cent of students failing to progress to second year, the highest dropout rate in the country. The sector is also struggling under the weight of student numbers that are increasing year-on-year as state funding decreases, something that the Minister for Education, Richard Bruton, told The University Times last month was putting “higher education under particular pressure”.

For some, academia is seen as a burden, not an exploration. The enthusiasm is not in finding answers, thinking critically or expanding the mind

Meanwhile, our youth unemployment rate stands at a staggering 17.1 per cent. There is a discrepancy between increased university enrollment versus decreased employability amongst the youth, with or without college qualifications. But is employability the correct measure of success at third level? Why are we all here anyway?

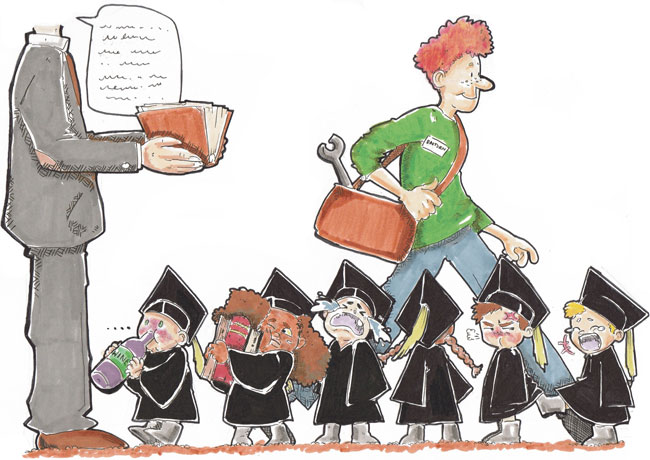

Universities began as places for those who desire intensive study of a particular field. Subjects were seen, in essence, as disciplines that require effort, initiative and motivation. For many middle class students, however, university is not a choice based on a desire for further academic study but rather as a “rite of passage” and the expected next step on the path towards adulthood.

Universities are sometimes portrayed as day care centres for young child-adults, where they grow up and learn essential life lessons while also drinking excessively. Certainly, I embrace all of the above, though I question whether university is a necessary component for such life learning. In certain cases, students are no longer as involved or interested in their coursework. For some, academia is seen as a burden, not an exploration. The enthusiasm is not in finding answers, thinking critically or expanding the mind. Instead, the focus lies in student life: going out, meeting new people and embracing new experiences. One must question the necessity of university for such adventures.

Students are instructed that university is an investment in their future. It is a means of guaranteeing a better earning potential and a more prosperous career. But is this assumption true? Multi-millionaires such as Simon Cowell, Richard Branson and Lord Alan Sugar never went to university and ended up being extraordinarily successful – Sugar’s estimated worth of £900 million is something that a degree in any field can’t guarantee.

It is daunting to face an unmapped career path without having attended third-level. Irrespective of our qualifications, we will encounter challenges in our new careers anyway, simply a few years later. But is this delay worth the years of financial duress that university brings to many? A university education has now expanded past its standard three to four-year term to encompass what is often a required master’s degree and PhD programme. This, in my view, is an unfair and unrealistic requirement for many. Furthermore, many graduates pursue careers in a completely different direction to that of their qualifications.

There are alternatives to university that can more effectively achieve the same goals. We face an ever-changing labour market, where new job titles are constantly emerging and an environment demanding agility, flexibility and adaptability is seen as standard. This market appeals to individuals with skills that university may bring to blossom, such as motivation, self-initiative and discipline. However, third-level education is not the only source of such teachings.

Secondary schools are moving away from rote learning and exam cramming and towards team-based learning and continuous assessment. In countries such as Switzerland and Germany, apprenticeships are a widespread and successful means of third-level education. Seventy per cent of Swiss 15 to 19-year-olds are in paid apprenticeships, where time is divided between a vocational school and the vocation itself. After three years, individuals choose between further vocational training or university.

The well-established concept of lifelong learning should also be encouraged, ensuring student motivation and certainty of what they wish to study

This system has proven successful for youth unemployment. Germany and Switzerland enjoy the second and third lowest rates of youth unemployment of OECD countries, at 7.3 per cent and 8.6 per cent respectively. Already, Solas, the further training and education authority, is hoping to expand its apprenticeship programmes in the next few years. The government’s recent Action Plan for Education also highlighted the importance of work experience and apprenticeships as part of a student’s education.

Change is needed whereby individuals can learn applicable skills within jobs immediately after secondary school. Apprenticeships offer the chance to earn whilst learning on the job and could be encouraged by subsidies. The well-established concept of lifelong learning should also be encouraged, ensuring student motivation and certainty of what they wish to study. A university education would become a support in one’s career instead of a shaky foundation. Such a change may reflect the changes needed to suit an increasingly dynamic job market.

University should be accessible for all and should not be a luxury available only to the elite, but it is an outdated notion to assert that university qualifications are essential for a good career. University should be a place for serious academic study, especially for those who seek a deeper understanding, not deeper pockets. Attending university is not entirely a necessity for “student life” either. Such enjoyment may come from simply being young.