Back in April, Trinity flew a flag at half mast in honour of Prof John Gabriel Byrne, a man who founded and led Trinity’s department of computer science from its foundation and beyond and the man who was largely responsible for propelling Trinity and Ireland to its world-leading position in the computing industry. As the flag fluttered above Front Square and College Green from its position over Front Arch, a different sort of commemoration for the man who passed away on April 16th was beginning in the Department of Computer Science and Statistics, from those whom he worked with, inspired and considered a friend.

Born on July 25th, 1933, Byrne entered Trinity in 1951 to study engineering. Ten years later, after studying in Birmingham and at Imperial College London, he began as a junior lecturer in the engineering school, one year before Trinity’s first computer, one of the first computers in the country, would arrive, and 30 years before the arrival of the internet in Ireland. This computer, an IBM 620, arrived on June 16th, 1962, in two crates and required a crane to lift it through the temporarily removed first-floor window of 21 Lincoln Place, now the location of Trinity’s dental hospital. At a price of £10,000 – somewhere between €200,000 and €250,000 today – the machine had a memory of 20k decimal digits – 0.00025 per cent of the memory of an 8GB phone. With no disk for storage, it also came with paper tape, a punch and an IBM typewriter.

The leader in the campaign to convince Trinity to purchase the machine was Prof William Wright, then Head of the School of Engineering, with Byrne, who had studied for his PhD under Wright, now a strategic ally. Only a handful of computers existed in Ireland at the time, and dominant belief was that we didn’t need any more. For Byrne and Wright, however, the computer was a necessity, and their persistence managed to place Trinity, and by extension Ireland, in a pioneering position.

We were selling time on the computer to companies in Dublin. We would run jobs for them, and it brought an extra income to further develop the system

Rosemary Welsh started working in the engineering department as a computer operator in 1963, the same year that the MSc in computer applications began. Speaking to The University Times, she describes how the College was “very slow” to come around to the vision Byrne and Wright had put forward, and so the department spent time showing others the machine’s worth: “We were selling time on the computer to companies in Dublin. We would run jobs for them, and it brought an extra income to further develop the system.” Before there was a degree programme in computer science, Byrne pushed against Trinity to introduce the College’s first evening course, a course in systems analysis and computer programming, which ran for two nights a week: “There’s a lot of history in trying to get that past the Board … He pushed forward, without a lot of support from colleagues.”

Dr Dan McCarthy was one of the lecturers employed to teach this course, which he describes to The University Times as emerging from Byrne’s “great foresight about what the effect of the computer was going to be on society”. Aimed at young graduates who were taking an interest in new technology but had no opportunity to be trained in it, Byrne also sought to equip people in the industry with these skills from “banks and revenue, other civil service departments, the medical service. Everywhere”. The success of the night time course helped lead to the introduction of the BA Mod degree programme, a course to which government funding was pledged and was, states McCarthy, “very successful in terms of numbers and saw a lot of those people go on to contribute to industry here and abroad”.

Byrne’s ability to predict the need for and worth of the computing industry impressed even his closest colleagues. Michael Nowlan, having completed the master’s degree in computer applications and worked in the department previously, began working as an assistant administrator in the department in 1979 where he then worked with Byrne directly for 16 years. Nowlan, who would later become director of the College’s IS Services from 1995 to 2007, recalls: “I was always saying that things can’t continue at the same rate they are now. And right throughout my career in Trinity, they did. He said ‘no, you’re wrong’, and he was right. He was always right. He had that foresight to know that things weren’t actually going to slow down. They were going to speed up.” Byrne advocated for issues that still need advocates today, be that convince the government of the importance of investing in the industry or the benefits that would come with introducing computing onto the Leaving Certificate.

He had that foresight to know that things weren’t actually going to slow down. They were going to speed up

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of the computing industry to the Irish economy. The information, communications and technology industry in Ireland employs more than 37,000 people and generates more than €35 billion every year in exports. Firms around the world make use of technological enhancements, with some going as far as to raise their office floors to keep the cable management out of sight (click here for examples). Ireland has become widely recognised as the heart of this industry in Europe, with nine out of the world’s top 10 global software companies choosing to have strategic operations in based in Ireland. It was in Trinity, only about a 10-minute walk from the area now referred to as the “silicon docks”, that Byrne had an idea of how this industry could grow.

The sector’s growth in Ireland can be put down to many factors. For McCarthy, Wright’s recognition that government and industry leaders would need access to computer education helped make the case that investing in computers was worthwhile and joining the European Economic Community meant that research funding programmes for education and computer science became available, an area in which Byrne was particularly proactive. McCarthy describes Byrne as “a man who would never take credit for it, but the right man in the right place at the right time”, a figure who was aided by emerging technology and attitudes but without which such growth would not have been possible: “He knew that computer technology was going to invade all sorts of places.”

Would the lack of Prof Byrne slow us down by 2 years, 5 years, 10 years?

It was this attitude that propelled Trinity into national leadership: “There was a famous endeavour to combine Trinity and UCD, with engineering going to go out to UCD, which would have made a lot of sense because engineering had been well-funded there. Trinity then ended up having a vibrant, expanding computer science department, which didn’t really happen in UCD. They had computers at the same sort of time that we did, but they didn’t have anyone in computer science education that acted in the way John Byrne acted. I think they lagged a long way behind.”

While it might seem a stretch to attribute the growth of Ireland’s most important industry to one man, his colleagues and contemporaries would argue just this. Speaking to The University Times, Dr Seán Baker, who began lecturing full-time in the department in 1982, states: “The big question for me is the role that Prof Byrne played in the development of the computer industry in Ireland and the computer departments in our universities and our ability to create high-quality graduates that are used in industry and elsewhere. If Prof Byrne hadn’t been here, if he hadn’t done what he did, there is no doubt in my mind that we still would have developed computer science departments in our universities, we would still have developed a software industry, a computer industry in Ireland. Without a doubt, we would have.”

“But we would have been so much slower to the party than we actually were. So would the lack of Prof Byrne slow us down by 2 years, 5 years, 10 years? And if, for example, we had been 10 years later in developing what we developed, we would undoubtedly not have the same position in the software industry in the world that we actually have.”

Much of Ireland’s economy and, indeed, its modern identity has come as a result of the strength of its computing industry, its high number of graduates and the number multinationals that choose base themselves in Ireland. The country has become one of the major software innovations hubs in Europe and one of the world’s major software exporters. How much of this was down to Byrne as an individual? “If it hadn’t been for Prof Byrne, you have to ask: would we possibly have this position? Would we have been so slow to the party that we couldn’t possibly be in the top positions that we’re in at the moment. Maybe we’d be number 20, or number 50, or number 100 in Europe or the world. We wouldn’t be in the position that we’re in without the contribution that he has made.”

Byrne’s colleagues are full of stories that prove just how far Trinity has come in this field. In 1968, the College’s computer was housed in a hut behind the physics building. When Welsh interviewed with Wright for the position of computer operator in 1963, she had to go out to the RDS where the College’s computer was at a science exhibition. When Dr Mike Brady, now an assistant professor in computer science, first started as an engineering undergraduate in 1971, punch cards were still the way that students learned programming, a method that meant students did not get near the computer itself. Brady tells The University Times of how “you had to punch up your cards, submit them to the woman, and she’d take them back. I think you got a receipt or something, and then the following day you got your results back. So you didn’t get near the computer.”

The fact was that he could talk to anyone as an expert, as the face of computer science in Ireland, this was just outstanding. There’s nobody like him

It was on June 17th, 1991, that the internet first arrived in Ireland. It arrived through IEunet, a Trinity campus company for which Byrne served as a director. The ethernet first came to Ireland through Trinity, too, installed in the department when it was located in Pearse St. As current students and staff bemoan the College’s WiFi network or online systems, it might be hard to accept the pioneering position that Trinity was, and to some extent still is, in. However, Nowlan notes that the department could always be ahead of the wider college system, adding that: “I may have been director of IS Services, but of course, I always deferred to him because of who he was.” For Nowlan: “The fact was that he could talk to anyone as an expert, as the face of computer science in Ireland, this was just outstanding. There’s nobody like him.”

One word that continually comes up when talking to those who knew and worked with Byrne is “shy”. “He was a very shy guy, amazingly shy”, remarks Nowlan. “He was very private in the dealings of the department. He kept everything in his head or he wrote it down in one of his little black books. Everything else was in his head. He wasn’t one for producing documents.”

It was perhaps because of this shyness that his ability to achieve his own goals was a source of continual mystery. “He seemed to always get his way”, Brady states. “How he did it, I don’t know. There were probably about a dozen people in the college that he seemed to get on very well with, powerful people that had his trust and he theirs. But it was a mystery to me.” “In the 16 years that I worked with him closely, he was highly successful in getting the resources that were needed, and he managed to manipulate things without making any enemies”, adds Nowlan.

Prof Neville Harris, who many highlight as one of Byrne’s closest friends and colleagues, notes that Byrne was “extremely, extremely quiet … None of us really got to know him completely because he only really told you things if he asked you a question.”

“It was only after he passed away that we realised he had so many interests or he knew so many people and so many interests that not many people knew about”

He’d know if someone got their hair cut and always complimented them, which was good for staff relationships, and people gave them a lot of loyalty because of it

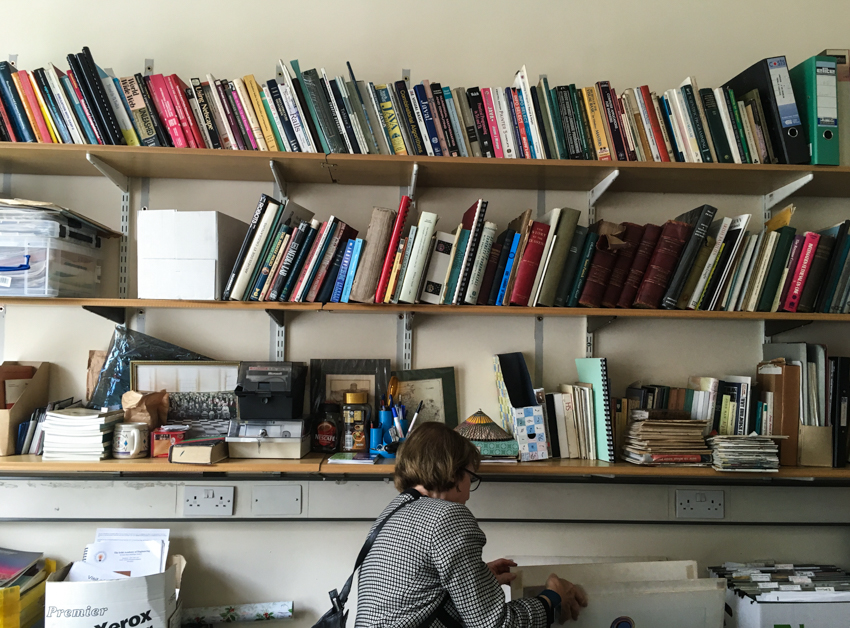

Despite Byrne’s evident talents, colleagues tell of his somewhat lacking abilities as a lecturer. Brady recalls: “He was a hopeless lecturer, really desperate. He’d be talking and turn to the board and scrawl something invisible and just mutter away, so you really had to pay attention. He was a terrible lecturer, really, and he never really got any better.” Byrne’s appearance too was typically shabby, and his office was filled with feet-high stacks of paper: “He was not the tidiest of people, but he always knew where everything was”, states Daphne Gill, who was hired as a secretary within the department. “That was the biggest thing for me, never to touch anything in his office, because he had his own filing system.”

While it seemed that many in the department found certain areas of Byrne’s character and habits to be mysterious, they were struck by how much Byrne appeared to know about their lives. Welsh recalls: “He’d know if someone got their hair cut and always complimented them, which was good for staff relationships, and people gave them a lot of loyalty because of it.”

When Brady had a baby in 1985, he was teaching on the night course: “Without even asking me, he took me off the night course. He just said ‘you’re on the day course now.'”

John had encouraged three of the nursing staff to go forward and get further qualifications in their career. They were so fond of him that they actually took these steps

It was these actions, combined with the excitement of the new discipline, that produced awe-inspiring loyalty from his staff. Welsh recalls that “because it was new, and people were enjoying it, they put in extra time. When we needed things, people would stay in late”. Byrne would also inspire and encourage others to strive within their education: “When I left school, I wouldn’t do anymore study, but he was encouraging me to go and get a professional qualification”, says Welsh. “That, I think is his greatest contribution. He could always encourage people to go and extend themselves a bit further.” A member of the nursing staff later told Gill that, during Harris’s oration at Byrne’s funeral, she wanted to hold up something of a sign to commemorate the influence he had on their staff. “John had encouraged three of the nursing staff to go forward and get further qualifications in their career”, recalls Gill. “They were so fond of him that they actually took these steps.”

Most of those who worked with him call him “Prof Byrne”, “JGB” or simply “Prof”, a symbol of just how rare a professorship was back when Byrne first got his. If this suggests that the relationships they forged with Byrne were not personal, this was not the case. When Byrne moved to the nursing home in Newtown, Harris visited him every Sunday. “He was maybe my best friend. I even knew him better than I knew my brothers and sisters because I worked with him, and I nearly lived with him, bringing him home every day. He wasn’t just a colleague, he was a friend. A friend from then right up until he passed away. I think the loyalty that he inspired for the people who were close to him toward the end of his days is just a testament to just how fond we were of him. There were few departments who worked along those lines, that instilled that loyalty.” Many more visited him, including both Gill and Welsh, with Neville remarking of Byrne’s relationship with his female colleagues: “A lot of them were like daughters to him. And when he got sick, they looked after him because he had nobody else.”

For Gill, such visits were a chance to give back to a man who had influenced her life so strongly: “It was a lovely privilege when he was needing slightly more help to be able to offer that help. I was retired at the time and I could give him that, all that he had give me when he was young. That was a lovely thing to be able to do.”

It was a lovely privilege when he was needing slightly more help to be able to offer that help. I was retired at the time and I could give him that, all that he had give me when he was young

These friendships were formed between those working in the department at every level. Gill recalls that the youth of the department’s staff and their discipline aided such bonding: “To this day, we have terrific friendships, 40-something years later. We had terrific fun outside of office hours, we used to go waterskiing, we used to go camping, we used to go hillwalking.”

Since Byne’s passing, the question has turned as to how to best commemorate him. Speaking to The University Times over email, Dr Chris Horn, who is spearheading a new book about Byrne and his influence, including submissions from colleagues, family and friends, explains that he hopes the book will “a warm memory of the influence he had on so many people”.

Speaking to Byrne’s closest colleagues and friends reveals too many stories of pioneering and influence to include in any one article. His work with the library, his interest in the arts, his love for rugby and horse racing – these are memories dear for those who were close to him. For te who knew him best, this ongoing task of commemoration is one that continually pulls up new stories too. “There’s so many things like this that we should have done with him”, notes Harris, “and we’re all regretting not doing them”.

For Harris and his colleagues, Byrne’s legacy is an important one worth commemorating: “I might be over-exaggerating, but he was a real Trinity man through and through. But a lot of people might not have known that he existed because he was in the background. He’s John.”