When reading the annals of Trinity from two centuries ago, a lot is familiar. They mention names of fellows and scholars that now annotate lecture theatres and refer to societies that we knew about before even coming to Trinity. However, when you read the College Calendars and come across a magazine that appears in the 1800s with a completely alien title, it’s intriguing.

The Dublin University Magazine was a literary and political journal founded by Isaac Butt, John Anster and John Francis Waller, with its first issue appearing in January 1833. All the founding members were students of Trinity, but the magazine wasn’t college affiliated. They decided to launch this magazine with the objectives of “discussing the new developments and defending the Tories”. It had a significant presence on campus and enjoyed popularity at the time. It was a conservative publication launched in response to an increasingly liberal population on campus. As the years progressed, the magazine increasingly became dedicated to publishing literature, with the final issue being released in 1882.

Although its name is unfamiliar to most, the story of its foundation mirrors that of today’s new conservative magazine, the Burkean Journal. Both started by Trinity students, not officially affiliated with the college and reacting to a more liberal population on campus. It says something about the cyclical history witnessed in the timelines of Trinity’s societies.

Over the last three hundred years, the lives of societies have proved to be fluid. Some become defunct, some are reincarnated and some are expelled from College before making an indignant return. Two of our best known societies have gone through these times of decline and obsolescence.

Over the last three hundred years, the lives of societies have proved to be fluid. Some become defunct, some are reincarnated and some are expelled from College before making an indignant return. Two of our best known societies have gone through these times of decline and obsolescence. Dublin University Philosophical Society (the Phil) and the College Historical Society (the Hist) both claim inception dates so far back into history that they can’t be formally corroborated. The title of the world’s oldest student society is one claimed by both, but according to 19th-century College Calendars, neither are as old as they say.

At one time or another, these societies were considered defunct. Even their origins are informal, the Hist beginning as a nascent club, a meeting borne out of frustration with a lack of academic motivation. “Burke’s Philosophical Club”, according to Stubb’s History of the University of Dublin, felt that “formal course of university studies was not a sufficient stimulus to the students of more active minds for the fullest cultivation of their intellectual powers”. It’s easy to blur the lines between a few friends reading a paper and giving themselves an esoteric name, and an active effort to establish an institution dedicated to a certain endeavour.

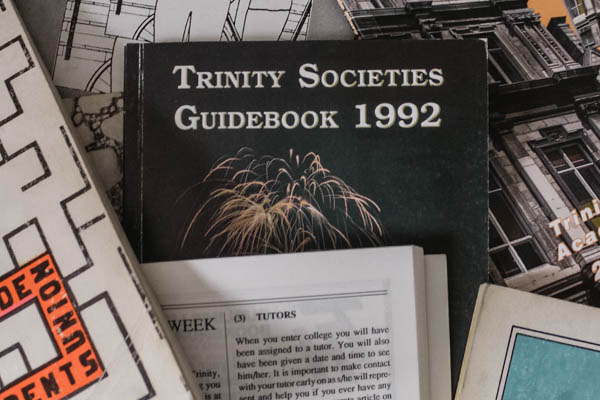

All existed before the Central Societies Committee (CSC) had laid out stringent guidelines in forming and running a society. In the early days, the College Board oversaw society affairs, “granting chambers” to societies and clubs. However, as societies have grown in number and in individual size, the need for targeted regulation is evident. Fiona May, Secretary of the CSC, keeps a comprehensive list of defunct societies within the CSC’s lifetime. She explains the function of the body, that “if a society is inactive for two years, they are inactive according to CSC constitution”.

Each society has to draw up a constitution and keep the committee up-to-date with their activity. Since the CSC was only established in 1969, their records are limited. However, within this extensive list you can see all the failed attempts by students to start a dedicated club. Joseph O’Gorman, Strategic Development Officer of the CSC and an Assistant Junior Dean, said to The University Times, that students often come to them with “that moment of ‘hey I’ve got a great idea’” and while the CSC “encourage what we can”, they often have to tell students that “that ain’t a great idea, no”.

Some only exist for a couple of years, like the Stamp Collecting Society of 1997, while some are infiltrated by other societies and taken over.

As it stands, student laziness is a major contributing factor to many societies failing. Some only exist for a couple of years, like the Stamp Collecting Society of 1997, while some are infiltrated by other societies and taken over.

While rifling through the brittle spines of College Calendars from 1846, it’s easy to become frustrated with the tedious exercise of tracing back a society that hasn’t existed for almost 200 years. However, if anything, a trip to the Manuscripts and Archives Research Library is one every student should make, even if it’s just for the cloak-and-dagger excursion of having Old Library security guards usher you discretely from room to room, giving only vague directions to the elusive library’s location, an experience that ultimately ends in a run-of-the-mill office that contains a very special book collection. Within these records, and those of the CSC, there lies a special history which would be a shame to forget.

The Fishing Society is one that many older students remember fondly, as it’s one of the most well-known defunct societies in Trinity, running from around 2011 to 2014. Like most other lost societies, they died out because of a failure to submit reports. However, while their constitution listed their aims as promoting the pastime of fishing, they had a habit of spending their funding on nights out, all while under the guise of a fishing society. They submitted reports and provided enough evidence to the CSC that they were, in fact, a legitimate fishing society, all while it wasn’t much of a secret that they didn’t spend their days fishing.

As the rumour goes, their society status wasn’t rescinded because of this, it was because they were simply inactive for two years and therefore defunct in the eyes of the CSC. They existed once as Trinity Anglers and claimed to engage in fishing-related activities, endeavoring to “tackle the Irish Seas and reap the boundaries of waters foreign”. Whether they did or not is uncertain, but stories from students of this time all follow a similar narrative and it seems clear very few fishing rods were involved.

The One World Society was an arguably successful group that existed between 1982 and 2007. It had a few names, including the “Third World Group”, “Impact” and “Nicaragua Libre”. Their aims were centred around global awareness and fundraising. In the constitution, their objectives included things like “promoting the welfare of the poor in the Third World” and “promoting issues of social justice”. In the chairperson’s report of 1994, it listed events like the Concern All-Ireland Final and other events like “The Faculty Waits on You” dinner. They organised African Dance parties in Doyle’s multiple times due to popular demand.

Most defunct societies tend to have relatively short lifespans, but One World was around for 25 years. While it enjoyed popularity early on, attention ran out for One World. There’s no scandalous story as to why it became defunct, it just seemed to have run its course. However, today their aims are being fulfilled by societies like Trinity Global Development Society and Society for International Affairs (SOFIA).

The Fortean Society is one whose reincarnation is unlikely, as according to the CSC, if they were formed today they would not be ratified but ushered into Trinity Sci-Fi Society. Their aims were laid out to “provide a forum for the discussion of experiences falling outside the scope of contemporary science”. They formed in 1994, and hosted a selection of talks from “Technopagans” to ghostbusters and others on topics like witchcraft. They struggled with committee problems throughout their run, opening their report from 1997 with: “Well, we had a year.” Gaining more than 140 members during their opening year, this provided “evidence of a good deal of interest among the student body in the world of unexplained phenomena”. The same year they spent £100 on candles and incense. They ran essay competitions, UFO debates, published a monthly Fortean Times and a bi-monthly Pagan Dawn. They began to meet more serious issues after “years of difficulty” and eventually became defunct in 2002.

Trinity had its own Anarchist Society, with the objective of implementing the slogan of “organise, agitate and educate” by providing a forum for discussion of anarchist theory. Ironically, they fizzled out because they simply didn’t do anything at all.

From 2003 to 2009, Trinity had its own Anarchist Society, with the objective of implementing the slogan of “organise, agitate and educate” by providing a forum for discussion of anarchist theory. Ironically, they fizzled out because they simply didn’t do anything at all. By not turning in secretary reports, the CSC listed them as inactive, although it can be argued that an anarchist society could never exist formally, due to the need for compliance with the required committee hierarchies. In 2007, they logged no committee meetings and throughout their run they submitted only two secretarial reports.

One society in particular has escaped all scrutiny and acknowledgment since the 1840s. This is the University Reading Society, which was as prevalent and advertised as the likes of the Phil and the Hist. Today it is completely unknown. The society bears a resemblance to the Literary Society (LitSoc) of today, as it aimed to promote literary exploration and afford opportunities to socialise. It was founded in April of 1839, according to the ever-thrilling College Calendars of the time. It had its rooms in House Four and boasted a lending library. Their rooms were supplied with the leading newspapers of London and Dublin and many important journals of the time.

It had a full committee, consisting of a president, treasurer, secretary and librarian, and a member list like that of the Hist in the same year, with lifelong members as well. They awarded prizes to the best prose essays and the College Calendar published the names of the successful writers each year. What seemed to be a healthily functioning society suddenly just stopped appearing in the calendars from around 1849. Perhaps it’s fair to say that once a society is no longer functioning it died for a reason, but important institutions like the Phil and the Hist went through the same fluctuation of student interest and battles for existence. It’s hard to imagine that a Trinity without either would be the same.

Each of these societies, some remembered fondly and others long-forgotten, added something to student life and had members dedicated to its success. This seemingly small part of the fabric of our college has such a rich and varied past. Seeing how long societies have been around and how important they are to Trinity’s culture, remembering and recording our vibrant societal past, should not escape from our priorities.