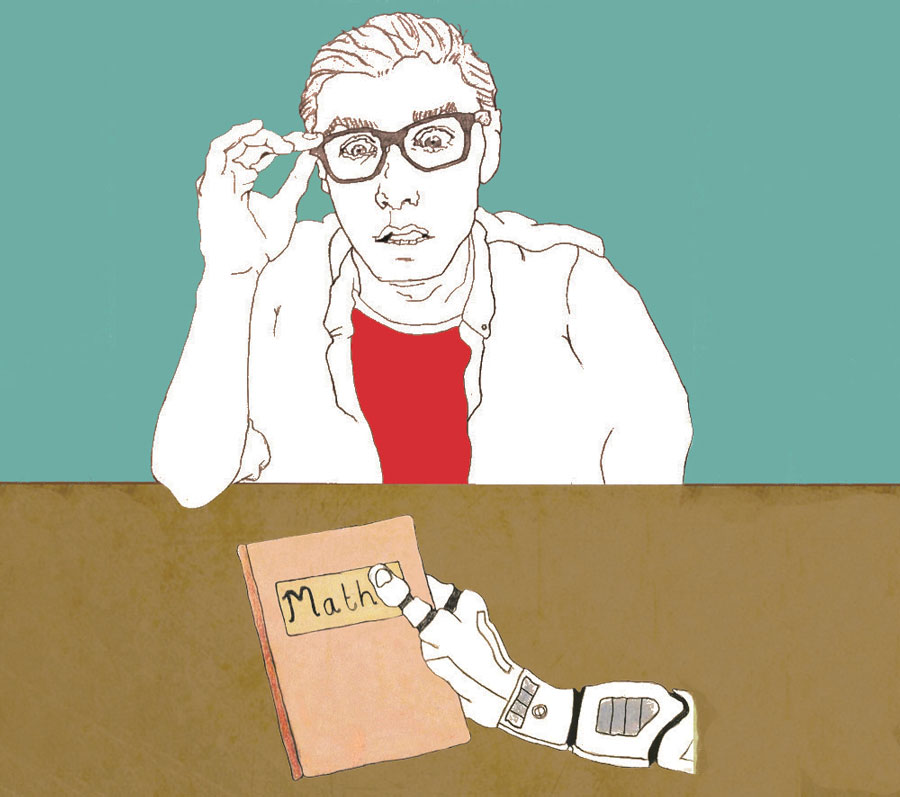

For many, the dystopian impact of artificial intelligence on society is a fearful one, never mind letting it run loose in a classroom – a sanctuary of learning, betterment and safety.

To have this haven of humanity become victim to the rise of automation fiercely clashes with all our perceptions of teaching as a quintessentially human task. However, the infiltration of artificial intelligence in education should not engender fear, rather, curiosity and open mindedness. If we both embrace and implement the available technology correctly, we will be on the cusp of a very exciting change in education.

Artificial intelligence is present more than ever in our society: facial recognition at passport control, Siri, online customer support and the recommendations provided by Spotify and Netflix are but a few examples.

Whether we like it or not, the day is dawning when it will soon seep into classrooms and lecture theatres. Its integration into our education system seems almost inevitable. Faced with this reality, we must carefully consider how we’re going to use it, not only to garner its full potential, but to ensure that we remain in control and avoid fulfilling the sci-fi movie prophecy of a human world controlled by robots.

Artificial intelligence, the imitation of human intelligence by machines, can have a dual role in education, acting either as a facilitator or as an educator. For example, in its role as a facilitator, artificial intelligence would assist in carrying out time-consuming tasks such marking exams and keeping track of homework submission. Thomas Arnett, a senior research fellow at the Christensen Institute with a focus on education, sees this as positive progress for the future of teaching, stating, “While AI won’t replace teachers, what it can do is start to substitute some of the tasks they do, so teachers have more capacity to focus their time and energy on the activities that are of most value to their students.”

This type of artificial intelligence could change the dynamic of third-level education, which, at present, tends to take the form of a large number of students having little one-to-one contact or engagement with teachers. Arnett hopes that if artificial intelligence is put to use as a facilitator, it could free up time for lecturers to engage in discussion and debate, assist in lab activities and set aside more time for office hours.

On the other hand, if allowed, the technology is at such an advanced stage that it is technically capable of teaching a class, acting in place of a human educator. Artificial intelligence education technology is able to mimic the bare minimum of a teacher’s role through knowledge of the subject being taught and teaching methods employed. This level of capability has prompted the fear that the teaching profession is, like many job these days, at risk of becoming automated and carried out by robots.

With this major fear in mind, it is somewhat reassuring that among experts in the field of artificial intelligence education, it is practically unanimously agreed that an artificial intelligence-based tutor will never be capable of matching the role of a human teacher. According to Wayne Holmes, lecturer in education and technology at the Open University, it cannot deliver the “human aspects of teaching”. The inability of artificial intelligence to understand emotional intelligence and lack of contextual or subjective intelligence is proof of this, Prof Luckin highlighted when speaking to The University Times. Whilst it can mimic human emotions, it has no real grasp of them. Its understanding is rooted in machine learning and it lacks the ability to respond to the needs and variables of each individual situation. The development of emotional intelligence is something most humans do as they grow older, with some exceptions such as in those who have conditions like autism. However, not everyone develops at the same rate, leaving some setting out on careers that require the ability to form relationships, without the tools to do so. Many employers now invest in executive coaching for this reason, which teaches employees how to be more emotionally intelligent. There is no option to do this when it comes to artificial intelligence.

Given these possibilities, a question then arises: what can and what should artificial intelligence be used for? Whilst it is capable of both learning and teaching, perhaps its capabilities would be better served in teaching humans about learning. When speaking to The University Times, Dr Luca Longo of Dublin Institute of Technology’s School of Computing pointed out that artificial intelligence can open the “black box of learning”. Artificial intelligence technology can teach us about how learning occurs, tracing the path taken by a student to eventually arrive at an answer, and detailing things like how long it took them to get there and how many mistakes they made before settling on their final answer.

Another of artificial intelligence’s more favourable qualities is its ability to “data mine” – the process of combing through colossal amounts of data and information in a timeframe human will simply never be capable of. The technology then identifies patterns in such data and extracts from it the most useful information. Arnett sees this as a great tool now available to teachers. It enables them to carry out more sophisticated searches when researching content for lesson plans, offering the potential for fine-tuned classes catering to students. Essentially, it’s adding to their teaching, rather than replacing.

While not only allowing for more tailored lessons for classes of students, artificial intelligence technology can provide personalised learning experiences for individuals, through an Intelligent Tutoring System.

These systems can help to resolve the problem of teaching to different “types” of learners – the technology can judge the learner’s capabilities and provide them with the most suitable content, whether it be audio, visual or text.

From all of this information, it’s evident that there is no shortage of ways artificial intelligence can be deployed in education, but how do we go about this is in the most effective way in order to take full advantage of its capabilities? It appears the risk with artificial intelligence is not its automation of teaching, but rather the way we approach it. As Arnett cautions: “We have to be careful of what it is we’re expecting the technology to do and what it is we’re hiring it to do.”

The fear is that, given the technology is technically capable of doing a lot of their jobs, teachers will take a back seat and let technology do all the work.

Another risk, more in line with our fear of an apocalyptic world dominated by robots, is the exploitation of the technology by policy-makers and the government. This is where the threat of automation becomes more real and more frightening, as it’s not difficult to imagine a world where artificial intelligence tutors could be viewed as an easy, cost-effective alternative to human teachers. They don’t take sick days, they don’t go on strike and they’re a once off investment. As Luckin points out, “the commercial enterprise is building these systems and not necessarily going to point out its limitations”. Wayne Holmes agrees, warning that we must “start with the learning and not be seduced by the technology”. Therefore, as we stand on the cusp of a potentially dramatic change to education, the conversation must be led by those equipped with a deep understanding of artificial intelligence – both its strengths and inadequacies.

If we afford artificial intelligence education the opportunity to improve itself, it can make up for some of the pitfalls in education. Accepting that human teachers will not and cannot do everything allows us to make room for artificial intelligence, ultimately improving the overall education experience for everyone. Just don’t expect robots to take over just yet.