Like all issues in education policy, access to education is complex, nuanced and difficult to adequately address. Nowhere is this issue more pressing than in Northern Ireland, where educational inequality has been the topic of a seemingly endless barrage of reports and studies, all bemoaning a system that remains out of reach for many.

It’s a well-documented fact that inequality persists in Northern Irish education. In 2015, a report published by the Equality Commission found that working-class Protestant boys underperformed in their GCSEs and A-Levels compared to their Catholic counterparts. Politicians and academics have all had a go at diagnosing the problem, with some citing the traditionally strong influence of Catholic schools and the politically charged nature of school selection as reasons for the disparity.

The legacy of the Troubles has clearly impacted and exacerbated this problem, with the post-conflict nature of Northern Irish society throwing up social hurdles for those seeking to enter higher education. Divisions in academic achievement are perhaps unique in Northern Ireland, with class, religion and politics all combining to create complex problems that offer no easy solutions.

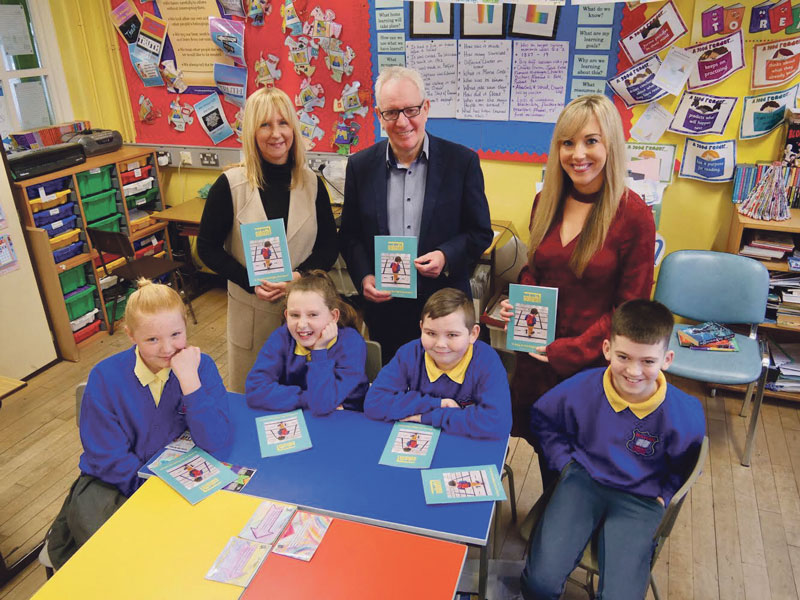

Attempting to combat this is the Goliath Trust, a charity that aims to increase equality in education through “early intervention” in underfunded primary schools. Established last autumn, the charity, which has received backing from the likes of Tony Blair and Bertie Ahern, plans to provide targeted financial support to 12 schools in Northern Ireland, encouraging the development of disadvantaged students.

The reality is almost one third of our young people are not adequately empowered

Speaking to The University Times, Executive Director Caroline McNeill explains the need for such a concerted fight against educational underachievement in the North. “We’re often told by facts, figures and the media here in the North that we’ve an excellent education system and at the top end we do.” However, she says, “the reality is almost one third of our young people are not adequately empowered and not being able to reach their potential”. Thirty per cent of Northern Irish children leave primary school unable to adequately read or write.

Describing the main causes of this inequality, McNeill cites poor mental health as a key contributing factor, acknowledging that parents’ own situation in terms of the Troubles and how they’ve been impacted is now beginning to have a knock-on effect on children in terms of their mental health and wellbeing. While she is acutely aware of the fact that such an issue “could equally be found in inner city Dublin or Limerick or other parts of the island as well”, she also claims that “I suppose it’s particularly pertinent here because of the legacy of the Troubles”.

While mental health is a topic of growing concern worldwide, the issue is particularly pronounced in the North. Research conducted at Ulster University recently found that 30 per cent of Northern Irish citizens suffered from mental health issues, with over half of these cases being linked to post-traumatic stress from the region’s history of conflict. Figures have shown that Northern Ireland has higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder than other politically fraught regions such as Israel and the Lebanon and since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement suicides rates have almost doubled. In addition to this, research has shown that these issues are just as prevalent among so-called “ceasefire babies” born after the conflict’s formal conclusion.

While mental health is an “absolutely huge” issue, McNeill also describes difficulties in helping “newcomer students” – refugees and immigrants – to assimilate in education. This is a problem that clearly needs tackling, with some Northern Irish schools developing an unfortunate reputation for high levels of “prejudice-based bullying” and reports showing that minority ethnic pupils are more than twice as likely to become unemployed than their peers.

“Here we’re used to two communities, simply orange and green, but now it’s a more diverse society so there’s real challenges around that because some people from some communities are maybe uneasy with their child sitting beside a child from another country”, McNeill says. This issue becomes even more challenging when one considers the fact that “the newcomer pupils have their own sense of trauma from where they’re coming from”.

These issues are clearly informed by the legacy of unrest and unease in the North, but the core of the problem is universal. Speaking to The University Times, President of the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation, John Boyle, describes how educational underachievement can occur in any society. He explains that often students from disadvantaged backgrounds “have dropped out of the system long before entry to third level”, as they have “either literally left the system or mentally and emotionally disengaged from formal education”.

Each and every child enters a primary school with a dream that he or she can be and will be anything they want to be

“Each and every child enters a primary school with a dream that he or she can be and will be anything they want to be”, he says. Due to the tiered nature of the education system, however, “teachers who see the bright eyes of four-year-olds can often see their dreams shatter, their hopes fade and their expectations lower as the realities of their lives begin to dawn, for some at early and middle classes in the primary school”.

Director of the Trinity Access Programme (TAP), Cliona Hannon, has similar things to say about the impact of poverty on education. As she explains to The University Times, “potential is affected by poverty and limited access to resources. That doesn’t mean it goes away, but it does mean it is more difficult to prove through accepted metrics that the potential exists”. While “academic talent exists across the socioeconomic spectrum”, Hannon describes how “the main barrier to access by some socioeconomic groups is academic attainment”, something unfairly influenced by the “cultural capital advantages available to others” within the school system.

The sufficiency of government response to this issue, on both sides of the border, is up for debate. Minister for Education and Skills Richard Bruton has described access to education as a “priority” for the current government and reasonably successful schemes aimed at encouraging educational achievement such as the National Access Plan for Higher Education have been implemented in recent years. Despite this, Boyle argues that “too many initiatives in the area of disadvantage fail to have the intended impact because they neglect the root of the problem, which is poverty”.

“We have got to move from haphazard and ad hoc government initiatives to comprehensive, determined provision for disadvantaged children”, he said. Hannon similarly feels that the problem needs to be viewed in light of broader, harder-to-tackle issues, claiming that the government has failed to provide “enough targeted investment in tackling educational inequality and its systemic links with other facets of socioeconomic disadvantage”.

McNeill raises similar concerns about government spending in the North: “I’m sure it’s the same in the South, but departmental budgets here are being slashed and that impacts all schools. But for schools in disadvantaged communities with particular problems it only makes the gap even wider”, she says, voicing what’s becoming a common worry among educators in Northern Ireland.

After last year’s budget was released, a joint statement from leading figures in Northern Irish education warned that unless education spending was increased significantly schools could have to reduce subject offerings, increase class sizes or even shorten the school day. This was followed by the news that over 600 schools in the region had their budget plans rejected by the North’s education authority earlier this year, forcing them to reduce and review their spending plans.

Still, students and universities can and should try to combat the problem. As McNeill explains: “It’s about saying ‘look, what are our resources?’.” She explains how students themselves can help by getting involved in outreach programmes, describing it as “deeply rewarding for students to give up their free time and see first hand some of the challenges that teachers are facing in education nowadays”. Although Hannon recognises that universities can’t solve these societal issues single-handedly, she claims that “as privileged, (substantially) publicly-funded institutions, they can do a lot” by working with schools and pushing for educational reform.

Boyle, meanwhile, sees the issue as one that requires input from those beyond the narrow world of education, describing how we must collectively strive to “change an education system that shuts out the potential of bright, committed young children in disadvantaged areas as they approach the upper limits of compulsory schooling” and “encourages, if not pre-determines, that children opt out of formal schooling at a young age”.

While this issue may seem insurmountable, McNeill is confident that any step in the right direction is worthwhile: “It’s not that the trust has all the magic answers and we won’t be able to have an endless supply of money to support the schools, but it’s all about targeted intervention, so where we see that there’s need, we want to at least support principals as best we can.”

In addition to this, she describes how some of the trust’s operations can have an impact in terms of optics: “We have an eclectic board made up of representatives of the four main church groups here in Northern Ireland, which I think is very symbolic.”

Regardless of what form decisive action in the future may take, one has the feeling that now may truly be the time for tangible change to occur. Ultimately, the attitude of many increasingly seems to correspond with those working to make education more accessible, more obtainable and more just. As McNeill astutely puts it: “We all have an ongoing duty to inspire and lift young people, wherever they may find themselves.” If the trust’s strong public backing is anything to go by, this duty doesn’t seem to have gone unnoticed.