With 2018 marking the centenary of the end of World War I, November 11th undoubtedly took on a greater poignancy this year. This was made evident in the heightened number, scale and variety of the ceremonies that took place across the world in the week leading up to Remembrance Sunday. The amount of coverage these events received, and the degree to which controversy could flare up over who did or didn’t attend which ceremony and who said what about them, speaks to the sensitivities that lie around the issue.

Nowhere, perhaps, is the delicateness surrounding Remembrance Sunday, and the poppy on one’s lapel, more acute than in Ireland. Whatever it might be attributed to, however, in recent years there appears to have been a growing consciousness of the need to commemorate the war.

But a broader discussion of the matter is not to be had in these pages, and nor was it to be had on November 10th at 11am, when a small gathering of Dublin University Football Club (DUFC) members, current and former, was held in the 1937 Reading Room to lay a wreath at the base of the memorial constructed there in 1928. Carved into three white marble slabs are the names of some of the 471 Trinity students, staff and alumni, that died in World War I, mostly in the service of the British Army.

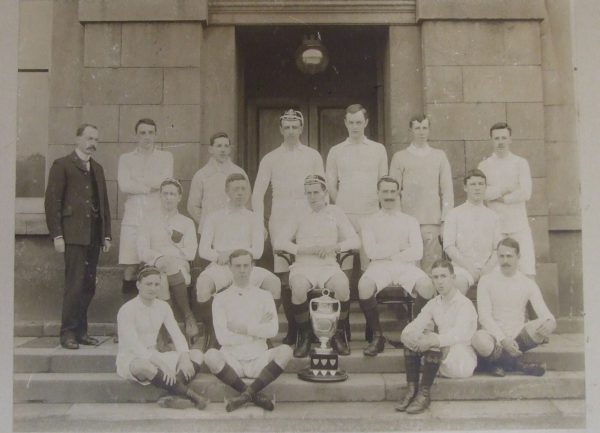

Forty-six of these names belong to members and alumni of DUFC and it was to these that those in attendance paid tribute. Among this number, and included on the list, are the names Reginald Bateman and Arthur Bateman, two brothers who graduated in 1906 and 1914 respectively and who were both killed in France in 1918. The Bateman Cup, established in 1922 and won by DUFC in 1926, was named after the pair. Also on the list is one Robertson Smyth (1879-1916), who captained DUFC’s first team in the 1902/03 season before going on to win three caps for Ireland and play in games during the 1903 British and Irish Lions tour of South Africa. He died on April 5th, 1916, while recuperating from the effects of two gas attacks.

The world’s oldest college rugby club in continuous existence – a fact that remains one of DUFC’s proudest distinctions – actually suspended playing between 1914 and 1918 due to the fact that virtually every member of the club between 1912 and 1914 enlisted in the war effort.

Neither of the two official histories of DUFC made mention of DUFC’s war dead, so it was up to the club’s recently appointed archivist, Stephen Odlum, to recover the details

Three of the players on the last pre-war first team, including Captain GE Bradstreet, never returned to play.

Though Provost Patrick Prendergast takes part in similar memorials, this is the first year DUFC have held a ceremony of this kind. So why only now? Speaking to The University Times, DUFC Chair John Boyd explains their reasoning. The idea was floated earlier this year when, in the run-up to the centenary, other Dublin-based clubs started to gather and present information about their members who were killed in World War I. DUFC’s members were asked if they knew anything about links between former members and the war effort, and Stephen Odlum, the club’s recently appointed archivist, set to the task. Neither of the two official histories of DUFC, written in 1954 and 2003, made mention of DUFC’s war dead, a reflection perhaps of the reservations of Irish public opinion towards the war, so it was up to him to recover the details of the careers of the deceased.

It was when attention was drawn to a particular name on the memorial that the idea of commemorating the club’s war dead began to really take shape. Samuel George Stuart (known as Sam) a Donegal-born Trinity scholar, gold-medallist, Fellow, DUFC first team captain and major in the Royal Field Artillery, was killed on October 27th, 1918, just two weeks before the war ended and not long after he refused to take the leave he was due. Stuart is buried in La Vallee-Mulatre Communal Cemetery Extension, but a plaque to his memory is fixed on the inside of the College Chapel in Front Square. This, and the memorial that was held on the centenary of Stuart’s death by his family, prompted the DUFC to return to the issue.

This story got Boyd, and the members of DUFC’s Executive Committee, thinking about the relevance the story held for the club in the present day. “We have an approach in the rugby club around respect. And we have a really rich narrative, in terms of the history of the club”, Boyd says. It’s a history that includes people like Charles Burton Barrington, a founder of what was to become the Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU), whose work helped codify the rules of rugby and mould it into the game that’s so popular in Ireland today. It is the example of Barrington that Boyd uses to illustrate his point.

At club meetings, he recounts, “I really made the point to them that Charles Barrington was just a student like you”. No different and no less worth emulating were the students of the generations heading into World War I. “They took great responsibility, they were innovative and you know, they added value … I said, ‘it’s up to you to make something of us, you know, make your mark’. Add to what’s gone before.”

Whether the war was right or wrong is a different issue. They thought they were doing the right thing, helping other people, doing their duty, taking responsibility

It’s interesting how abstract the specific issue of Armistice Day becomes in my discussion with Boyd, and it becomes clear that Remembrance Sunday, in the glow of a century’s worth of ritual commemoration, seemed not only a fitting occasion to remember the war dead but also served as a prism through which the club could refract its core values and project them onto its members.

Lest the specific occasion be forgotten in these thoughts though, Boyd draws attention to the particular resonance of the call and response between the lines of Colonel John McCrae’s poem “In Flanders Field” and Moina Michael’s poem “We Shall Keep the Faith”. In the latter of these, Michael, the American woman who pioneered the whole project of supporting veterans and using the poppy as iconography, wrote: “We caught the torch you threw/ And holding high, we keep the Faith … fear not that ye have died for naught/ We’ll teach the lesson that ye wrought/ In Flanders Fields.” It’s a direct reference to the verses in McCrae’s poem, which read: “To you from failing hands we throw/ The torch; be yours to hold it high/ If ye break faith with us who die/ We shall not sleep, though poppies grow/ In Flanders Field.” It’s the sentiments expressed across these poems, one of which marks the wreath laid by Sam Stuart’s family, “that’s what it was all about, as far as we were concerned”, says Boyd.

The organisers were far from oblivious to the sensitivities around the matter, and Boyd says the reception to the idea of the ceremony was “mixed”. “Whether it was right or wrong is a different issue. They thought they were doing the right thing, helping other people, doing their duty, taking responsibility. There are lessons here.” In the end, it was only a handful of the Executive Committee, and the captains of the women’s and men’s teams, who went to lay a wreath.

It is a testament to the those who survived the war, and the example set by those who didn’t, that the club managed to come out of the shadow and to thrive in the years that followed

Even with a generation of talent decimated and the shadow of war cast long over the nominally small club, DUFC won the Leinster Cup in the first post-war season. It is a testament to the those who survived the war, and the example set by those who didn’t, that the club managed to come out of the shadow and to thrive in the years that followed. If this was what the memorial was supposed to draw attention to, then the point was probably well, albeit quietly, made.