Many barriers exist for Irish Travellers – but especially in education. In 2000, Traveller-only classrooms, where Traveller children were made to wash before entry into the classroom each morning, were still in use. Up until then, Traveller children were given separate lunchtimes so that they would avoid interactions with their settled counterparts. The perception that Travellers did not have the capacity to be taught prevailed – teachers therefore refused to educate them and left many of these children illiterate.

Prejudice against Travellers persists to this day. Anti-Traveller rhetoric is deeply embedded in society, with research showing that 63 per cent of Irish people reject Travellers on the basis of their “way of life”. But what does the non-Traveller Irish population understand of this “way of life”?

“There are so many stereotypes and omissions of what Travellers are and what they stand for”, Independent senator Colette Kelleher tells me. Kelleher describes the history of the travelling community as “a missing part of the puzzle of the history of Ireland”.

According to Kelleher, schools have failed to acknowledge Traveller culture and history – and this, she says, “feeds prejudice and discrimination”.

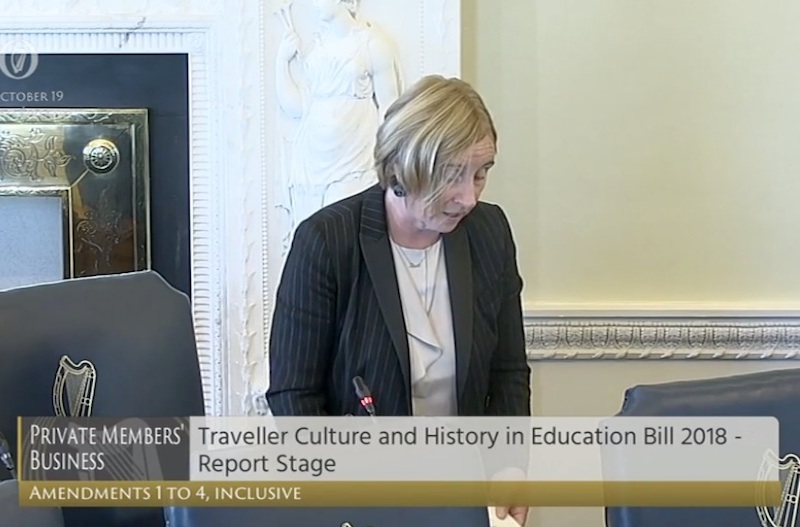

Irish Travellers exist outside the narrative of the country’s history. The Traveller Culture and History in Education Bill – which Kelleher introduced to the Seanad in July, 2018 – seeks to integrate the history of the minority population into the school curriculum.

There are so many stereotypes and omissions of what Travellers are and what they stand for

The bill’s aim is to foster a more welcoming school environment for Traveller children and to serve as means by which the myths and lies that underpin the racism, prejudice, and discrimination that Travellers experience on a daily basis can be pulled apart. Last October, it passed its final stage in Seanad Éireann and has since been forwarded to Dáil Éireann.

“Traveller culture and history is something which is important for all students”, Kelleher insists.“In terms of having a more rounded and respectable view of Travellers, it is necessary for all pupils to learn the facts, the truth and the joys of Traveller culture and heritage.”

At present, settled children do not learn about Traveller culture in a positive light – or at all – which increases “the chance of their views being formed by the negative stereotypical views of Travellers that persist in wider society”, Kelleher says.

“It is also necessary for Travellers to see that their particular culture and history is recognised and valued”, she adds.

The Traveller Culture and History in Education Bill, Kelleher says, is an important step in acknowledging that culture and history belongs to all members of society – including those who have been disempowered and dispossessed.

Patrick McDonagh, a Traveller and current PhD student in Trinity, has long been interested in the origins of his community. He says, however, that “it is hard to learn your history when nobody is teaching it”. McDonagh had a “mainly positive” experience in education, but recognises that his reflection is unique.

It is hard to learn your history when nobody is teaching it

Kelleher stresses that “school still remains a cold place for Travellers”. The incredibly low number of Travellers in higher education can be traced back to the fact that many in the community leave education at an early age. The national average of people who sit the leaving certificate is 73 per cent – among Travellers, it is just eight per cent.

Nationally, 86 per cent of people aged between 25 and 34 have achieved a second level education – only nine per cent of Travellers have. This data links directly to primary and early secondary education, where there is often a lack of understanding among educators and peers.

Artist and Traveller Leanne McDonagh, who works as part of an access team in Cork Institute of Technology to encourage those from a Traveller background to engage with third level education, tells me that she has seen “teachers make assumptions about the traveller community without realising that I am a traveller, or that I am related to some of the kids”.

“I have experienced authentic reactions which have not always been pleasant. To be honest, I have to open people’s eyes to the stereotype that they have”, she adds.

“When I was a student, I never thought that I would become an art teacher or that I would be able to exhibit my work”, McDonagh tells me. “There are many artists, who don’t even think to call themselves as such, simply because they don’t have a qualification.”

Most damaging of all is the fact that the diversity of the Travelling community goes unrecognised by the Irish population. Travellers, McDonagh says, are not a homogeneous group with identical views. “Travellers”, she insists, “deserve to be recognised for who they are as individuals”.

For her, the bill is crucial to amplifying the Traveller voice in Irish society. “The media has destroyed the community for so long – yes, there is a percentage of the community that are criminals, as in every community, but the positive stories are not shown”, McDonagh continues. “There are Traveller nurses, frontline workers, doctors, teachers, solicitors – but they are not willing to come forward and speak out.”

The media has destroyed the community for so long – yes, there is a percentage of the community that are criminals, as in every community, but the positive stories are not shown

“A lot of people hide their identity as they are afraid that it will affect their employment or position in society”, she adds.

In Ireland, of working graduates, 90 per cent find employment in Ireland with an average starting pay of €33,000. However, according to the 2016 census, just 0.5 per cent of Irish Travellers continue onto higher education and graduate with a qualification. For many, these figures provide statistical proof of the destructive impact of institutionalised racism.

For an ethnic minority group numbering less than 45,000, Travellers in Ireland continue to face considerable stigma. Patrick McDonagh reminds me that not so long ago, presidential candidate Peter Casey claimed that Travellers should not be recognised as an ethnic minority because they are “basically people camping in someone else’s land”.

McDonagh is “hesitant to say that there has been a shift in attitudes” since this time. “Being a Traveller is not a lifestyle choice but, rather, an integral part of the group’s identity”, he explains.

Travellers are one of the most historic groups of people in Ireland – McDonagh says that “some members of the Traveller community hold onto nomadic ways that were seen in Ireland’s pre-colonised landscape”. The group has a distinct language (De Gammon) and has a tradition of piping and music, of tin-making and storytelling. During the Easter Rising, Travellers used their wagons to help rebels smuggle guns – most non-Traveller readers will be oblivious to this fact, as well as many other contributions that the community has made to Ireland’s past.

But the new bill working its way through government is bent on ensuring that Traveller history and culture will “appear in history, music, art and design, different civil rights and equality lessons”, according to Kelleher. “There will be no given lecture but will appear as a normal and mandatory part of all of the different modules that children and students engage with”, she says. “[It] will be woven through all different parts of the curriculum, so it would be vertical and horizontal in terms of the components in the primary junior and senior cycle curriculum”.

The inclusion of Traveller culture and history in education means that students will begin to look at the Irish Traveller contribution to the World Wars, the Easter Rising and the Civil War. Kelleher is sure of this, and tells me that she is guided by one, single principle: “When we know better, we do better.”