James Shaw and Ciar McCormick

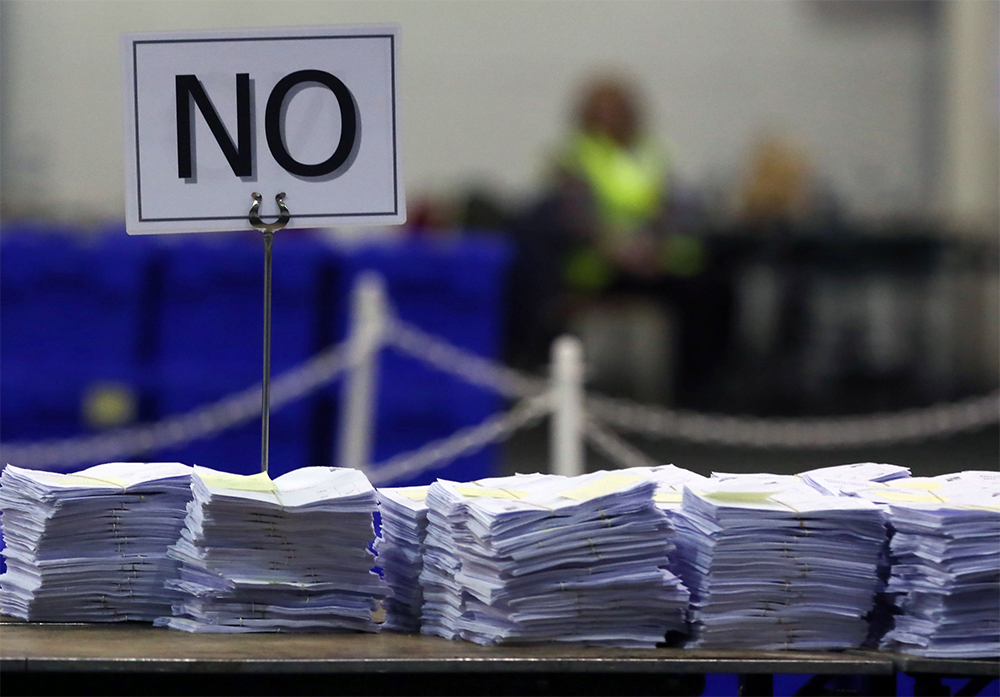

Scotland’s resounding vote against independence in last week’s independence referendum can, pessimistically, be seen as a defeat for democracy. The decision gives validation to those who fear that politics are subservient to corporate interests. But, a week on, a closer look at the results should leave room for optimism.

The blatant bullying campaign waged by business and media interests was an embarrassment to the democratic system. Only one major newspaper, The Sunday Herald, endorsed a yes vote, while most major publications actively opposed, including the Guardian, The Economist and The Financial Times. The mainstream media clearly backed a negative stance toward independence.

85 per cent turned out to vote, which is both unprecedented and particularly ironic for a referendum initially decried as unnecessary

Furthermore, chief executives of companies ranging from Shell to Baxters endorsed a no vote. Major Scottish businesses, such as The Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), threatened to move down south to England if the yes vote had passed. The Scottish National Party (SNP) denied that this would affect employment and claimed that such moves would be mere brass plate migrations. Regardless, there was clearly a concerted campaign of negative coercion. Corporations did not want Scotland to be independent.

A majority of Scots, including many on the no side, agree that they would like to see an independently flourishing Scotland. That is why voters were made to fear that an independent Scotland could not survive economically. While that was always a possibility, there are many small economies thriving around the world that provide counterfactual examples, with Ireland being just one.

The level of fear mongering these past few months has been shameful. This was a referendum rather than a general election, and as such voters had the opportunity to implement real, concrete change. More importantly, it was a referendum spurred by a grassroots movement. A yes vote could have renewed a faith in democracy in the same way the American Revolution inspired the French. People might no longer fear wasting a vote by opposing the status quo.

Unprecedented Positives

But even though the SNP did not achieve their intended goal, they have succeeded in providing a viable alternative to political cynicism. The independence movement went from 30 per cent to 45 per cent support in less than a year, and legitimised claims for some form of radical action from Westminster. The energy that fuelled this movement can be built on in the near future.

History may one day count this vote as a win for democracy

In another positive sign, 85 per cent turned out to vote, which is both unprecedented and particularly ironic for a referendum initially decried as unnecessary. This turnout was the highest seen in any vote ever taken in Great Britain, and is a testament to the hard work done by the SNP to promote discourse on the topic.

The voting age was lowered to sixteen for the referendum. This action was surprisingly effective in getting younger people interested and involved in the decision making process. The Guardian reckoned that 71 per cent of 16–17 year olds voted for independence. 48 per cent of 18–24 voted yes and 59 per cent of 25–34 year olds voted the same way. These statistics show a strong concentration of youth voters interested in independence. The SNP can take this support and build on it to deliver the changes promised by Westminster. Furthermore, a large portion of the No vote came from elderly voters in declining constituencies. The SNP may have lost this battle, but demographics could one day win them the war.

Another referendum looks increasingly likely considering the ground that the SNP made up over the past few months. Irvine Welsh argues: “the reason that this is such a bad result for the establishment is that it compels action; the narrow no decision, in tandem with the massive surge of momentum towards yes, leaves the issue unresolved. Though defeated in the poll, the independence movement emerged far stronger… The referendum galvanised and excited Scots in a way that no UK-wide election has done… Unless [Westminster] come up with a winning devo max [devolution] settlement, every general election in Scotland will now be dominated by the independence issue.”

While history has registered a loss for independence, it may one day count this vote as a win for democracy. The result has, for the moment, dispelled fears that cynicism and apathy are undermining civic interest. Rather than this referendum being the conclusion to the independence debate, it may ultimately be a stepping-stone toward something far greater.

James Shaw is a Contributing Writer to The University Times, while Ciar McCormick is Deputy Opinion Editor.