As the announcement of the date for the general election becomes imminent, with polling day on February 26th seeming likely, the approach that politicians have taken to higher education is strikingly similar to the treatment of the issue before the 2011 election.

The present crisis in higher education funding is, to a large extent, the result of a massive increase in the number of students attending third-level institutions. This crisis intensified during the Celtic Tiger years, with a decrease in exchequer funding precipitated by the economic crisis in 2008. State support for universities dropped from €1.6 billion in 2005 to €939 million in 2014 and, in addition, this has led to a 25 per cent decrease in state funding per student and a 30 per cent increase in student–staff ratios since 2008.

This striking decline has not been sudden. The immense strain on the public purse caused by the recession provoked this decline. Current problems facing higher education institutions existed to a certain extent before the election of 2011, albeit on a lesser scale. As early as 2010, the Irish Universities Association, which represents the presidents of the country’s universities, stated that the system of funding at the time was unsustainable due to a 15 per cent decrease in funding in the previous two years.

In spite of problems in higher education in 2011, a cursory glance at the principal election literature fails to demonstrate any sense of urgency on the issue, with higher education being dismissed with a few lines in each manifesto.

There is increasing engagement with the funding crisis in higher education, reflecting renewed desire to address the issue.

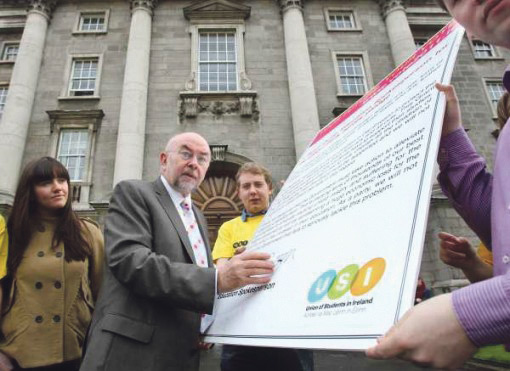

Ruairí Quinn, the then-Labour Education spokesperson, dramatically signed a Union of Students in Ireland (USI) pledge at Front Gate in 2011, committing to oppose and campaign against “any new form of third level fees including student loans, graduate taxes and any further increase in the Student Contribution” – a commitment he would renege on just several months later as the Minister for Education.

The contrasting promises of Fine Gael, the senior party in the eventual coalition, proved more influential in shaping education policy after their election. The party preferred the replacement of registration fees with a graduate tax. Proposals for increased efficiency, productivity from third-level staff and a restructuring of the third-level system were also put forward by Fine Gael.

Fianna Fáil, the outgoing government, seemed broadly in favour of retaining the existing scheme of funding over which they had presided whilst in government. They also proposed the provision of a higher education labour market fund of €20 million to allow people to retrain and access higher education after a period of long-term unemployment. Sinn Féin’s manifesto makes a passing reference to the party’s opposition to any increase in fees. However, a common theme running throughout the campaign is the lack of detail and attention from all parties on the issue of higher education.

This lack of action on higher education has undoubtedly contributed to the problem as it stands today. Even after the election of the Fine Gael and Labour coalition, the increase in student numbers and decrease in funding has continued to exacerbate the crisis in higher education. Yet, the future saw not just inaction, but active reneging on these promises. The “registration fee” has been replaced by a more accurately labelled student contribution of €3000, twice as high as when Quinn made his promise. As the funding crisis in higher education persists, this measure seems largely temporary. Further reforms are being formulated by the higher education funding working group, whose report has yet to be formally published.

Nevertheless, The University Times learned in December 2015 that the report is to outline a series of proposals leading to the introduction of income-contingent loans provided by the government, to be repaid by students when they acquire employment after graduation. This seems to have changed the substance of the debate among political parties. The discussion seems to have shifted from one extreme to the other – from abolishing fees to imposing an incoming-contingent loan system. Fine Gael’s proposal for a graduate tax prior to the last election has faded from the current rhetoric. Speaking at the Royal Irish Academy last September, Peter Cassells appeared to rule out this option.

Thus far, before the formal start of campaigning for the approaching election, parties have begun to reveal policy positions on higher education. Speaking at the Connolly Café Youth Forum this week, Jan O’Sullivan, the Minister for Education, has committed the Labour Party to the reduction of the student contribution by €500 and the establishment of a €25 million fund for the improvement of staff–student ratios within the first year of the next Dáil. The Social Democrats revealed on Friday that they would seek a reduction of €1000. Sinn Féin have called for the abolition of all financial barriers to education. By contrast, Renua Ireland, in their recently published manifesto, have advocated for income-contingent loans, something Lucinda Creighton, the party’s leader, outlined at the Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union general election debate last October. Fianna Fáil have taken an intermediate position. “We will not be supporting any further increases in student fees,” Charlie McConalogue, Fianna Fáil’s education spokesperson told The University Times, adding that “any increased funding over the coming years to ensure quality provision at third-level should be funded by the exchequer.”

There are signs that the nation is at last ready to address the difficulties facing third-level institutions, as parties begin to outline clearer positions on their education policies

There is increasing engagement with the funding crisis in higher education, reflecting renewed desire to address the issue. Another marked contrast between the pre-election discourse on higher education in the past few weeks, and that of 2011, has been the salience of student accommodation. A report published in December by the Private Residential Tenancies Board shows that monthly rent in Dublin for the month of September 2015 had increased by 8.7 per cent compared to those of 2014. Average rent was calculated at €1,265 for an apartment, which is only 2.3 per cent below the maximum attained in 2007 before the crash in housing prices. USI have called for an increase in housing to support the demand from the 80,000 students living in the Dublin area, as well as granting students’ unions the legal standing to challenge changes in rent on behalf of their members. The dearth of accommodation for students is an issue that will undoubtedly enjoy an elevated level of salience, given the connection of this issue to broader societal problems of homelessness.

In 2011, the funding crisis was obscured by the overwhelming impact of the recession and the banking collapse. However, there are signs that the nation is at last ready to address the difficulties facing third-level institutions, as parties begin to outline clearer positions on their education policies. One would hope that the problems impacting students, as well as broader societal concerns, mean that both established and emerging parties will give these issues the attention they deserve.