With the general election just days away, political parties have assured students of many commitments, including pledging not to increase fees over the next five years and even advocating for a system of universally free education. These pre-election promises are frequently derided due to the notoriously fickle nature of Irish politics. This is partly due to our system of proportionate representation, which, through ensuring a wide berth of representation, leads to coalitions and thus compromise on areas of policy. Faced with a litany of what appear to be half-promises, students are left frustrated at the uncertainty over whether or not they’ll be able to attend college if fees are increased.

In this situation we must be pragmatic, and think of both the need to fund our education system and the social duty to provide education that is accessible to all. Education is both a social good and a private one. Society benefits both economically and culturally from having a well-educated population. Likewise, the students who receive that education benefit as individuals, as well as contributing to society as a whole. It follows that those who benefit from a good should contribute to its cost, and so it is right that education should be funded primarily by the state.

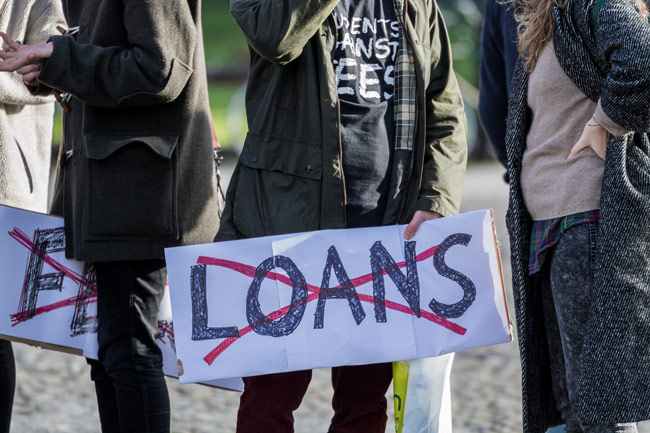

Additionally, the people who directly benefit from education should also contribute to its funding. However, the prospect of fee increases and the introduction of a loan scheme forgets the duty for education to be accessible and not the preserve of the wealthy. It does so by forcing many students to take on the burden of debt.

With regard to fees, a charge based on one’s ability to pay seems most progressive

Given the on-going funding crisis in higher education, we must consider alternative structures to funding our third-level institutions. With regard to fees, a charge based on one’s ability to pay seems most progressive. Under such a system you could have a minimum income threshold, under which only a nominal sum of €100 would be paid. For incomes above that level, education could be charged as a maximum percentage of household income, say 10 per cent, up to a maximum fee where the amount falls below that percentage. This would ensure that accessing education would not adversely affect a household’s standard of living. By having a maximum fee of, for instance, €10,000, the only people who would pay the full figure would be those for whom €10,000 represented less than 10 per cent of their household income. This model allows for funding where everyone contributes what they can afford and would put education within reach of all.

Speaking to The University Times by email, Prof John O’Hagan of Trinity’s Department of Economics expressed that the is good in principle, but wondered how this scheme would affect “students who have to live away from home, which adds hugely to the cost of university”. In this scenario, the cost of living away from home could presumably be met by a combination of private funding through part-time work or by some form of living grant. Alternatively, for those students living such a distance from the university that a commute is not feasible, they could pay less than the 10 per cent of household income for their tuition fees in order to accommodate their increased living expenses.

In a separate email exchange, Prof Brian Lucey of Trinity’s business department explained that funding for college comprises several elements: student fees, Higher Education Authority funding, and other elements such as research grants, charges and endowments. He stressed that student fees only make up about a third or a quarter of overall college funding. He therefore noted that funding would have be jointly tackled by the exchequer, students themselves, and from private funding in the form of co-ordinated degree programmes and grants. Lucey also pointed out that there is no evidence that reducing fees in Ireland has had a significant impact on participation rates at third-level to students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, adding that the foregone earnings from attending university for a number of years is a greater push-factor than the cost of college itself.

We must take into account that society benefits from education and that education – be it “higher learning” or vocational training – should be a realistic ambition for all citizens who wish to pursue it.

Granted, this is a hugely complex area and there is no magic bullet to solve all the problems of higher education funding in Ireland. However, at election time it is worth remembering that we don’t just live as individuals but participate together as stakeholders in society. This is why we have elections in the first place. We must take into account that society benefits from education and that education – be it “higher learning” or vocational training – should be a realistic ambition for all citizens who wish to pursue it. It is therefore crucial for society that education is not made further unaffordable by the introduction of a loan system to offset increased fees. As politicians stand for election and we read their manifestos, they would be well-served to remember that their purpose is to make a better society and not to pander to the electorate with false promises to gain power.

The tit-for-tat bickering of party politics must stop. Instead, politicians need to focus on working towards solutions that address our economic needs. While no system is or ever can be perfect, we can at least aim for practical solutions which reduce inequality and thereby benefit the majority without imposing an excessive burden on any section of society. By considering people’s ability to pay for education, we can ensure that it is both funded fairly and accessible to all.