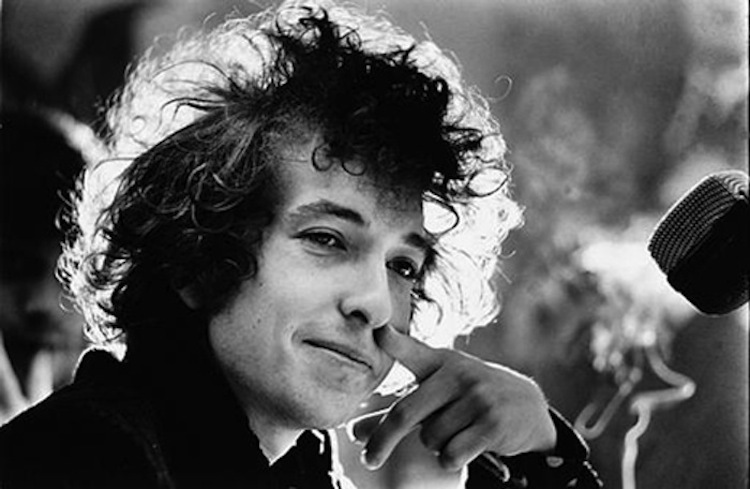

In the hours since its announcement, news of Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize for Literature has divided the devoted and indifferent among us. Despite having 50/1 odds of winning at the time, and being pitched against literary heavyweights such as Japanese author Haruki Murakami and Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Dylan was awarded the prize on the merit of his lyrics as detached from his music and “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” over the course of a career spanning 50 years, according to the Academy.

The idea of Dylan as a poet has ruffled more than a few feathers. Sure, his self-created image of a Greenwich Village bum, drifting from coffee shop to coffee shop, suits that of the beatnik poet, and certainly some of his lyrics remain as blisteringly relevant today as they did in 1962 when his first record, Bob Dylan, was released. But reactions so far suggest that there’s more to the award this year than just an appreciation of clever words.

Some have felt that Dylan’s award is to be taken as a statement that America has some true gems among its ditches, a timely reminder given the woeful political and social unrest plaguing its shores. Others have argued that it’s a move by the Swedish Academy, the body in charge of deciding the recipient of the annual award, to make the competition appear more inclusive, less elitist and to generate some popular discussion, a far more cynical reading.

Regardless of the arguments, what can be agreed on is that some statement – at the very least a suggestion, is being made on the nature of literature: what it looks or sounds like, who makes it, for what purpose is it created and who has the right to blur the boundaries of its definition? And who better than to reflect on these questions than Trinity’s own English scholars?

It is a vital record of the extraordinary story of America in the twentieth century

“

To those who know me my own personal feelings about Bob Dylan have always been plain: some years ago my mother advised me that she would have no objection to becoming Bob Dylan’s mother-in-law, if ever the occasion should arise. On the matter of the prize, I don’t think there can be any question over whether his work merits recognition of this kind. It is a vital record of the extraordinary story of America in the twentieth century, and of the people who have lived it, but it is not confined by its contexts. He is a master of language and observation, and there is a self-sustaining integrity and freedom to his work which another Nobel laureate, Seamus Heaney, was always concerned that poetry should preserve. I’m not at all uncomfortable with the designation of his lyrics as literature – in fact I’m delighted, and in a strange way even moved: because of his place in shared, popular culture his words belong to millions of us all over the world in a very special way. The real question, I think, is whether Dylan will accept the prize, but honestly it won’t matter if he doesn’t – the point has been made, and his remarkable achievements have been honoured.

—

Dr Rosie Lavan, Assistant Professor of Irish Studies. Her specialisation is in the work of Seamus Heaney, both as a poet and journalist, and contemporary Irish writing

It’s not often that somebody I’m actually interested in wins the Nobel Prize.

“

I think this is brilliant news. It’s not often that somebody I’m actually interested in wins the Nobel Prize. Bob Dylan has influenced the sensibility and expression of the western world, our forms of speech and of imagining. After all these years, something is happening and I do know what it is!

—

Prof Darryl Jones, Dean of the Faculty of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences. His areas of interest include horror fiction in Victorian and Edwardian literature and popular fiction. In years past, he has delivered public lectures on The Beatles

John Lennon must be turning in his urn

“

Great wordsmith, lousy melodist. John Lennon must be turning in his urn.

—

Dr Daragh Downes, a teaching fellow, specialises in the works of Charles Dickens and the Romantic period. Downes has also worked as a songwriter, and led the Album Review Club in the Irish Times for a number of years

Is it true that he ‘created new poetic expressions’? I don’t think so

“

Unlike a number of other major prestigious literary prizes and awards – the Griffin Poetry Prize, the IMPAC International Dublin Literary Award, or the Man Booker Prize for Fiction – the Nobel Prize for Literature is not restricted to particular genres. Since the Prize was first awarded in 1901, it has been given to poets, novelists and playwrights, but also to figures whose writings fall outside of these traditional generic categories. Bertrand Russell was awarded the prize in 1950 ‘in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought’. In 1953, Winston Churchill received it for his ‘mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.’ Last year, in 2015, the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Svetlana Alexievich, in recognition of her ‘polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time’.

It is tempting to see the award of the Nobel Prize to Alexievich as part of an attempt by the Nobel committee to broaden what it is we mean when we talk about ‘literature’ – with or without a capital L – by awarding it to a writer of non-fiction. The earlier examples of Russell and Churchill complicate that claim. To suggest, however, that the Nobel Prize for Literature has been awarded to Bob Dylan in 2016 because he ‘created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition’ is hard to substantiate. Yes, we can say that Dylan has made many brilliant, original and lasting contributions to ‘the great American song tradition’ – even if every single one of the terms used here is vague and problematic in its own way – but is it true that he ‘created new poetic expressions’? I don’t think so. To say that Dylan created ‘new poetic expressions’ in his songs is to ignore the ways in which his work from the very beginning of his career has engaged with and extended – but only slightly – the efforts of significant musical artists before him, among whom I would count Woodie Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Robert Johnson. Could one of them have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature? Why not? In the future, might the Prize go to other significant contributors to the American (and other) song traditions, from Elvis Costello to Tom Waits, Joni Mitchell to Morrissey?

Love him or hate him – and there are many who do – the Prize isn’t going to affect how people feel about Dylan’s music. The best we can hope for, I think, is that it may start to make people think more carefully about the meaning of ‘literature’ – what it is, and what its relation to other forms of expression, such as music, might be. That’s another way of saying that the Nobel committee’s decision to award the Prize for Literature to Dylan says more about the phenomenon of the prize itself than it does about Dylan. But it is also a way of saying that maybe it should have gone to someone more clearly committed to literary practice, which has never, really, been Dylan’s strong suit, no matter how closely Christopher Ricks and others have attended to Bob’s rhymes and repetitions. There are many others who are, in my view, more deserving of recognition, not least because they have made more significant and original contributions to our understanding of ‘L/literature’ than anything Dylan has done. In no particular order, I think I’d be happier raising a glass to one of the following this evening (with Dylan, perhaps, playing in the background): Margaret Atwood, John Ashbery, Joan Didion, Thomas Pynchon, Adonis…

—

Dr Philip Coleman, Associate Professor and Literary Arts Officer. Coleman’s general area of interest in modernist American poetry, with an especial focus on the work of John Berryman

Dr Rosie Lavan, Assistant Professor of Irish Studies. Her specialisation is in the work of Seamus Heaney, both as a poet and journalist, and contemporary Irish writing

“I think this is brilliant news. It’s not often that somebody I’m actually interested in wins the Nobel Prize. Bob Dylan has influenced the sensibility and expression of the western world, our forms of speech and of imagining. After all these years, something is happening and I do know what it is!

Prof Darryl Jones, Dean of the Faculty of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences. His areas of interest include horror fiction in Victorian and Edwardian literature and popular fiction. In years past, he has delivered public lectures on The Beatles

John Lennon must be turning in his urn

“

Great wordsmith, lousy melodist. John Lennon must be turning in his urn.

—

Dr Daragh Downes, a teaching fellow, specialises in the works of Charles Dickens and the Romantic period. Downes has also worked as a songwriter, and led the Album Review Club in the Irish Times for a number of years

Is it true that he ‘created new poetic expressions’? I don’t think so

“

Unlike a number of other major prestigious literary prizes and awards – the Griffin Poetry Prize, the IMPAC International Dublin Literary Award, or the Man Booker Prize for Fiction – the Nobel Prize for Literature is not restricted to particular genres. Since the Prize was first awarded in 1901, it has been given to poets, novelists and playwrights, but also to figures whose writings fall outside of these traditional generic categories. Bertrand Russell was awarded the prize in 1950 ‘in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought’. In 1953, Winston Churchill received it for his ‘mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.’ Last year, in 2015, the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Svetlana Alexievich, in recognition of her ‘polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time’.

It is tempting to see the award of the Nobel Prize to Alexievich as part of an attempt by the Nobel committee to broaden what it is we mean when we talk about ‘literature’ – with or without a capital L – by awarding it to a writer of non-fiction. The earlier examples of Russell and Churchill complicate that claim. To suggest, however, that the Nobel Prize for Literature has been awarded to Bob Dylan in 2016 because he ‘created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition’ is hard to substantiate. Yes, we can say that Dylan has made many brilliant, original and lasting contributions to ‘the great American song tradition’ – even if every single one of the terms used here is vague and problematic in its own way – but is it true that he ‘created new poetic expressions’? I don’t think so. To say that Dylan created ‘new poetic expressions’ in his songs is to ignore the ways in which his work from the very beginning of his career has engaged with and extended – but only slightly – the efforts of significant musical artists before him, among whom I would count Woodie Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Robert Johnson. Could one of them have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature? Why not? In the future, might the Prize go to other significant contributors to the American (and other) song traditions, from Elvis Costello to Tom Waits, Joni Mitchell to Morrissey?

Love him or hate him – and there are many who do – the Prize isn’t going to affect how people feel about Dylan’s music. The best we can hope for, I think, is that it may start to make people think more carefully about the meaning of ‘literature’ – what it is, and what its relation to other forms of expression, such as music, might be. That’s another way of saying that the Nobel committee’s decision to award the Prize for Literature to Dylan says more about the phenomenon of the prize itself than it does about Dylan. But it is also a way of saying that maybe it should have gone to someone more clearly committed to literary practice, which has never, really, been Dylan’s strong suit, no matter how closely Christopher Ricks and others have attended to Bob’s rhymes and repetitions. There are many others who are, in my view, more deserving of recognition, not least because they have made more significant and original contributions to our understanding of ‘L/literature’ than anything Dylan has done. In no particular order, I think I’d be happier raising a glass to one of the following this evening (with Dylan, perhaps, playing in the background): Margaret Atwood, John Ashbery, Joan Didion, Thomas Pynchon, Adonis…

—

Dr Philip Coleman, Associate Professor and Literary Arts Officer. Coleman’s general area of interest in modernist American poetry, with an especial focus on the work of John Berryman

Dr Daragh Downes, a teaching fellow, specialises in the works of Charles Dickens and the Romantic period. Downes has also worked as a songwriter, and led the Album Review Club in the Irish Times for a number of years

“Unlike a number of other major prestigious literary prizes and awards – the Griffin Poetry Prize, the IMPAC International Dublin Literary Award, or the Man Booker Prize for Fiction – the Nobel Prize for Literature is not restricted to particular genres. Since the Prize was first awarded in 1901, it has been given to poets, novelists and playwrights, but also to figures whose writings fall outside of these traditional generic categories. Bertrand Russell was awarded the prize in 1950 ‘in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought’. In 1953, Winston Churchill received it for his ‘mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.’ Last year, in 2015, the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Svetlana Alexievich, in recognition of her ‘polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time’.It is tempting to see the award of the Nobel Prize to Alexievich as part of an attempt by the Nobel committee to broaden what it is we mean when we talk about ‘literature’ – with or without a capital L – by awarding it to a writer of non-fiction. The earlier examples of Russell and Churchill complicate that claim. To suggest, however, that the Nobel Prize for Literature has been awarded to Bob Dylan in 2016 because he ‘created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition’ is hard to substantiate. Yes, we can say that Dylan has made many brilliant, original and lasting contributions to ‘the great American song tradition’ – even if every single one of the terms used here is vague and problematic in its own way – but is it true that he ‘created new poetic expressions’? I don’t think so. To say that Dylan created ‘new poetic expressions’ in his songs is to ignore the ways in which his work from the very beginning of his career has engaged with and extended – but only slightly – the efforts of significant musical artists before him, among whom I would count Woodie Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Robert Johnson. Could one of them have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature? Why not? In the future, might the Prize go to other significant contributors to the American (and other) song traditions, from Elvis Costello to Tom Waits, Joni Mitchell to Morrissey?

Love him or hate him – and there are many who do – the Prize isn’t going to affect how people feel about Dylan’s music. The best we can hope for, I think, is that it may start to make people think more carefully about the meaning of ‘literature’ – what it is, and what its relation to other forms of expression, such as music, might be. That’s another way of saying that the Nobel committee’s decision to award the Prize for Literature to Dylan says more about the phenomenon of the prize itself than it does about Dylan. But it is also a way of saying that maybe it should have gone to someone more clearly committed to literary practice, which has never, really, been Dylan’s strong suit, no matter how closely Christopher Ricks and others have attended to Bob’s rhymes and repetitions. There are many others who are, in my view, more deserving of recognition, not least because they have made more significant and original contributions to our understanding of ‘L/literature’ than anything Dylan has done. In no particular order, I think I’d be happier raising a glass to one of the following this evening (with Dylan, perhaps, playing in the background): Margaret Atwood, John Ashbery, Joan Didion, Thomas Pynchon, Adonis…

Dr Philip Coleman, Associate Professor and Literary Arts Officer. Coleman’s general area of interest in modernist American poetry, with an especial focus on the work of John Berryman