On an unknown date during my dad’s childhood, a rare and valuable book was bought in a flea market by his uncle Jim and placed in the bookcase in his family home. It was peered at every now and again, usually around Christmas, when one of us 20 grandchildren pulled it out to flick through its fragile pages much to the horror of the adults.

Why did my grand-uncle pick this seemingly innocuous book, not knowing its value at the time? Both he and my grandad had insatiable curiosity and fascination with Irish history, engineering and “useless knowledge”. Each would regularly travel to car boot sales and pick up books and random knick-knacks, often dismantling and reassembling them to varying degrees of success, before bringing them home to be examined and then left somewhere in the house.

But not this book. They quickly realised that it was worth something. It painted a picture of a long-forgotten Ireland, one of earls and dukes and grand estates. So it was looked after a little better than the other bits and bobs, enjoying a higher position on the bookshelf above the ancient, cathode-ray tube television, in the line of sight of my grandad’s armchair.

They were always curious from the get-go and they were always exploring

Toward the end of summer I was running my finger along the spines of the encyclopedias and other old books on the dusty old bookshelf. I picked this book out, remembering my dad talking about it years before, and recalled that at one point it belonged to our own house. Tracing the old maps and flicking through the ancient-looking pages, it made me wonder what the routes looked like now and how they had changed in the couple of hundred years since they were first drawn.

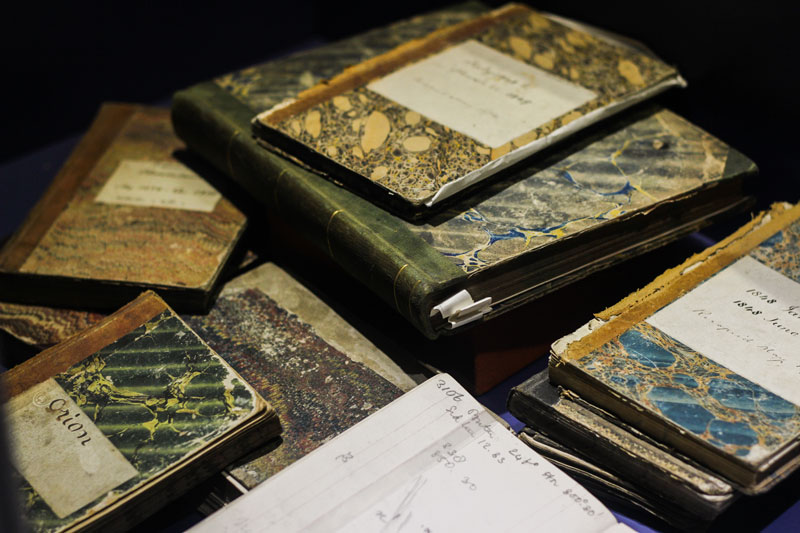

It wasn’t until my dad peered over my shoulder and began a long spiel on the importance of the book, Taylor and Skinner’s maps of the roads of Ireland, Surveyed 1783, that I understood the significance of the book, one of the earliest and most comprehensive road maps of Ireland. The first edition was created in 1777 by the two geographers, Andrew Skinner and George Taylor, and required an Act of Parliament to be made. “A new and accurate map of the Kingdom of Ireland from actual surveys by Taylor and Skinner” is the inscription on the first page. The Act was made on November 14th, 1778, and you could buy the book in Ireland for one guinea (about €175 in today’s money) from W Wilson in Number Six Dame St.

The book is leather bound, containing 285 pages of maps. When you compare the maps to a modern day one, they seem rudimentary or even slightly childlike, with little figures used to depict houses and lines spreading like veins across each page. However, our copy is even more interesting – it is complete. In many editions of similar ages, the maps and pages have been pulled, ripped or simply fallen out.

Curious, I began leafing through the maps to see if I could spot any castles, big houses or towns I would know today. To have your house or church or estate put on the map, you needed to pay a sum of money to the authors while they were travelling around. I came across the Dublin to Limerick map – a route I have travelled to visit my grandparents just outside Nenagh Co Tipperary nearly twice a month since birth. “His Majesty’s Castle in Dublin”, now more commonly known as Dublin Castle, was the starting point of all the maps. The names that most people would recognise would be the likes of Palmerstown House in Dublin or Castle Martyr in Cork. It also details ruins that are still there today, such as those on the Naas to Newbridge road in Kildare, which I discovered are called Jigginstown Ruins, much to my delight. And, surprisingly, the common ground of the Curragh and even a Curragh Racecourse existed back in 1777.

I decided to take my little car – affectionately called “Padre Clio”, as it came with a flaking Padre Pio sticker on its windscreen – on a road trip, following the map from Dublin to Limerick. And so, on a very cold Wednesday morning, I embarked on my journey.

First stop was Carton House. Growing up close to the demesne, which was transformed in the 1700s to the house we see today, I knew quite a bit about the history of the hotel and grounds. The Carton House demesne was the historical seat of the Earls of Kildare and the Dukes of Leinster. The demesne was transformed thanks to Lady Emily Lennox, great-granddaughter of Charles II, who married the 20th Earl of Kildare. She used her wealth to create the beautiful Shell Cottage on the grounds and the infamous Chinese Room inside the house, which was later used as a bedroom by Queen Victoria. The important thing to note with Carton, as well as with big houses across the country, is the role women played in their upkeep.

The changing landscape of Irish history would see the house abandoned after World War I

Next on my list was Emo Court in Co Laois, the old Queen’s County. Back then, Emo Court was far from the polished, neo-classical house it is today. The First Earl of Portarlington began its construction, but died before it was finished, leaving the second and third earls to complete the stunning building. The surrounding grounds and gardens of Emo are its true gem. Driving along the winding roads of the gardens, you can’t help but imagine a horse and carriage meandering through the autumnal colours of the trees to make it up to the big house.

The changing landscape of Irish history would see the house abandoned after World War I, the Easter Rising having created an unwelcome Ireland for Anglo-Irish Earls and protestants. It lay dormant, in the possession of the Irish Land Commission, until the Jesuit community took over in 1930. Novices would live in the adjacent wing for their two years of training. When talking to a staff member, I learned that this was not dissimilar to the first use of the wing, as bachelors that came to visit would be given a room there, away from the main house. In a sense, the rooms were always used by unmarried men.

Today it is The Cupcake Cafe for visitors and tourists. It’s hard to imagine what Taylor and Skinner would have seen when they arrived at the expansive estate of the First Earl of Portarlington, but I know for sure they would have soaked in the stunning views of the midlands that surround the house on all sides. The house was privately owned by an Englishman in the late 1960s, when Major Cholmeley Harrison, a former London stockbroker, purchased it from the Jesuit Order. Then, in 1994, it was donated to the people of Ireland and is now cared for and run by the Office of Public Works.

The abandoning of great houses was not an uncommon occurrence. Wealthy, usually Protestant, Anglo-Irish owners and tenants left the unfriendly lands of Ireland to escape the rapidly changing landscape of Irish politics as the country entered the 20th century. By the time the Irish Free State was established, very few remained in the country, leaving these grand dwellings unoccupied. In some places, the houses became the symbols of a hated elite or a former colonial power. In others, they were simply forgotten or ignored.

It was on my way to my next destination that I found myself recognising stretches of the road I was on. I had passed by these incredible, expansive estates of the once rich and powerful Irish aristocracy on numerous occasions to visit family. Yet never before had I noticed these opulent homes and estates. But perhaps this is the ultimate representation of what these estates became: forgotten. A part of the landscape to be passed by time and time again without a second thought or glance.

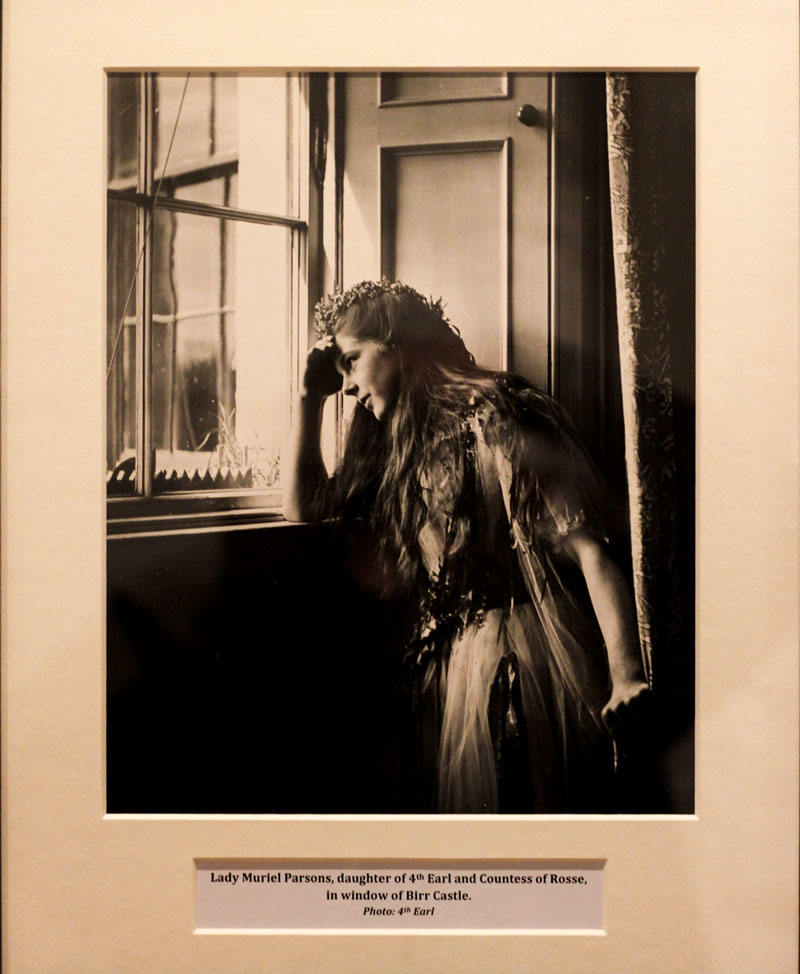

Not all estates found themselves facing such a sorry state, however. The Parsons family, in Birr, Co Offaly, were a curious bunch. Alicia Clements, descendant of the family and daughter of the current Earl of Rosse, told me they were like pirates: “No one could say no to them, and they were always curious from the get-go and they were always exploring.” They were not a noble family, as the first Parsons to occupy Birr Castle inherited the title from an uncle who died without an heir. Why was their curiosity important to their survival? When the Irish Famine struck, the Third Earl of Rosse – world renowned for his telescopes and stellar discoveries – and his wife, Mary Field, used their inheritance to fund as many engineering and building projects they could think of to keep the people of the area employed and fed.

Their contribution to the people of Birr meant that they were looked upon favourably and people viewed their scientific and engineering endeavours as a source of pride for the town. In fact, despite the lull in activity from the family after World War I, the castle was never looted or burned down like so many others from my book.

One such burning down by angry locals, and looting of granite window sills and fireplaces, was at Castle Otway in Co Tipperary. From the top of Keeper’s Hill, across from my maternal-grandad’s house, you can peer down into the valley below and catch sight of the castle’s ruins sitting prettily by the Nenagh River. A fascination of my childhood and subject of many a poorly constructed school history report, the castle is now overrun with ivy, has no roof and two large trees occupy its centre. The castle that originally stood there was taken over during the Cromwellian Plantations of the mid-1600’s and given to the Otway family. It was in the mid 1700’s, not long before Taylor and Skinner’s visit to the castle, that the fine house was constructed in front of the tower castle.

Some of the descendants that lived in the castle between the mid-1700s and 1922 are associated with notorious stories. Allegedly, Thomas Otway was cruel to his Catholic servants and banned them from taking days off on holy days. To mend his predecessors wrongdoings, the next head of Otway built a church for the Catholics. Today it is the Protestant church, after an argument between the locals and the castle’s next occupant led to the family reclaiming it for their own use. Some of the Otway family are buried below the Protestant church, with Protestants and Catholics (including my ancestors) in the graveyard that surrounds the church.

Not all estates found themselves facing such a sorry state

Emo Court was nearly abandoned and sold during the Famine. From my travels and research, it is clear that this was a turning point for the big houses – how the families handled it would be their making, or their demise. Otway’s occupants escaped back to England and away from the Irish. Despite Sophie Otway-Cave donating money to the local poor house in Borrisoleigh over the course of the Famine, the big house was set alight in the late 1800s.

Both the castle and grounds were regarded as beautiful in their day. Today, when you take in the spectacular views around Tipperary mountains, it’s not difficult to see why.

Most of the houses on the map, when it was created, may have just been estates in their infancy, however today they now make up the elegant “old” country hotels, or they have been taken into the care of the state to be enjoyed by everyone, or they are ruins in a cattle field along a busy motorway. One thing is for sure though, very few remain in the hands of those who did even before World War I, let alone 1777. Those that have, like Birr Castle, are an exception to the rule.

On a cold frosty evening in the waning light, sitting on top of my car – both of us muddy and tired from the long trip – you couldn’t ask for a more peaceful moment to contemplate the history of the houses and ruins I’d visited.

Maps, of course, are political by their very nature. Taylor and Skinner were certainly not Irish. But it would be wrong to argue that we can’t read something of Ireland’s history in their map. And even if the significance of these houses have faded, their grandeur lives on. I’ve walked their halls and stared out at Ireland through their windows. The country might have changed, but we can’t consider our history without retracing the steps that led to the rise, fall and return of our big houses.